Start the votes

It would be easy at this point just to make a list and have done with it. Announcing an election standing in the pouring rain with no umbrella while being drowned out by a song associated with another party’s landslide victory, asking people in Wales if they’re looking forward to a football tournament their team didn’t qualify for, taking questions from people wearing hi-vis jackets who turned out to be Conservative councillors rather than workers at the warehouse he was visiting, admitting there will be no flights to Rwanda before the election but refusing to honour a charity bet about whether there would be flights to Rwanda before the election, posing in front of an exit sign, inexplicably visting the Titanic Quarter in Belfast only to be asked by a journalist whether he was captaining a sinking ship. In fact, it was easy at this point just to make a list, so I did. It is fair to say that Rishi Sunak’s election campaign has not got off to an auspicious start.

One gaffe is a gaffe. A rolling clown show of hilarious unforced errors is a narrative. It’s tempting to think the Tories are trying to lull their opponents into a false sense of security. But sometimes, when you’re on the ropes getting repeatedly punched in the face it’s not a rope-a-dope strategy: it’s just you on the ropes getting repeatedly punched in the face.

This isn’t supposed to be a Substack about gaffes, and I’m not an election reporter. I’m trying to write about political attack, and dividing lines, and we’ve got to the point in the election cycle where dividing lines come into their own. Dividing lines are central to election campaigns, because elections are all about choices. Plan/no plan. Change/more of the same. Security/risk. Future/past. Investment/cuts. Hope/despair. Many/few. They contain positive and negative at the same time: vote for us/don’t vote for them. You can’t have one without the other. If the other party isn’t bad, then the positive reasons to vote for you are less compelling. If there aren’t any positive reasons to vote for you, then it doesn’t matter as much that the other party is bad.

Parties can run with more than one dividing line at once, and they often do, but they tend to go with one big one to frame the campaign. These are rarely surprising - it would probably be a mistake if they were - and they’re not this time either.

The Tories are leading with the one they’ve had for a while: plan/no plan. This was the theme of Sunak’s election launch speech, and the theme of the first tranche of Facebook ads sent out immediately afterwards:1

There are of course a number of problems with this dividing line, the most obvious of which is that nobody knows what the Tories’ plan actually is because they never get round to telling anyone, while Labour talks about its policies all the time. Indeed, just last week - as discussed in my previous post - Keir Starmer announced six “first steps for change” he would take if elected, as the initial moves in what he explicitly describes as a “decade of national renewal”. You are quite entitled to think that this plan is rubbish, but not that it doesn’t exist.

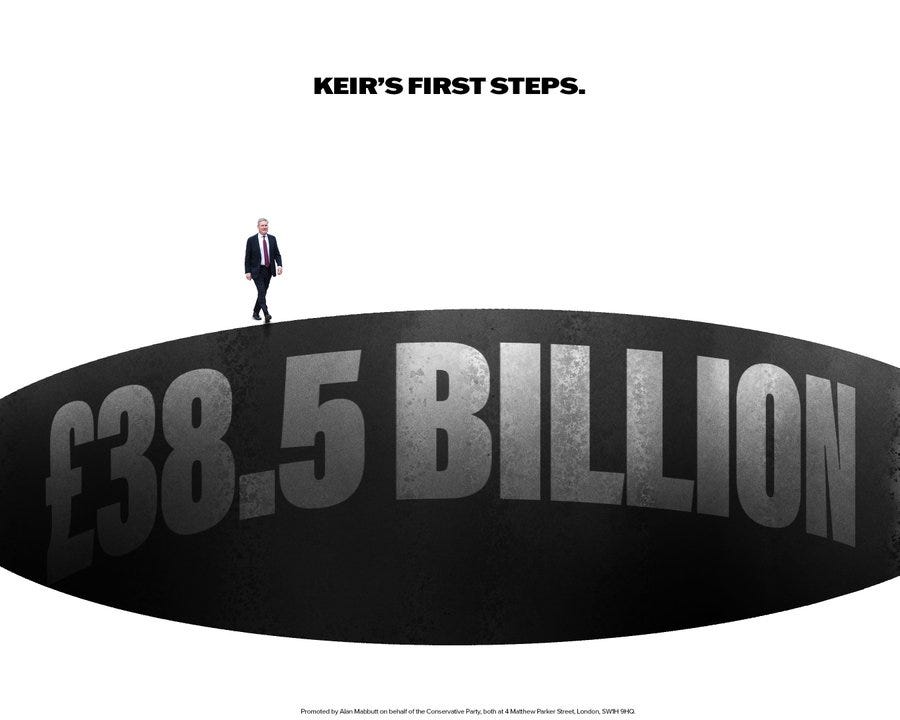

Indeed, last week the Tories launched another staple of governing party election campaigns, a spending dossier laying out what it claimed were the costs of a big set of Labour policies, including costings carried out by Treasury officials on the basis of assumptions by special advisers.2 It’s a £38.5 billion black hole, they say, and here’s the hole (it doesn’t really look like a hole, my brain processed it as a big bomb, but whatever):

Labour disputes many of the assumptions in the dossier, and its rebuttal document is quite fun. But the relevance of that for now is that it is very hard to square “look at all of these Labour policies, here’s what they cost” with “Labour hasn’t got a plan”, because the entire attack relies on looking at Labour’s plans and assuming that they are actual plans. Which may help to explain why Jeremy Hunt’s speech launching the dossier does not include the argument that Labour has no plan.3

The other glaring problem with this dividing line, which to be fair to the Tory staffers who designed this graphic is not something that they could reasonably have been expected to predict, is that it was being offered up by someone whose planning skills do not extend to looking at a weather forecast and responding appropriately to the news that it is about to rain.4 One of the contrasts between the Conservatives’ election launch and Labour’s response an hour or two later was that Keir Starmer was indoors and, consequently, dry. This is not a dividing line that anyone saw coming, but it is quite stark.

It plays nicely into Labour’s chosen frame for the election, which is change/more of the same. Labour has quickly shifted the branding on its website to a big “Change” banner, and failed to pass up the opportunity for a really obvious, but also funny, response to Sunak’s soaking:

The change line is a pretty standard one for an opposition party seeking to replace the government, but so far Labour are executing it well.

As I said, parties can run with more than one dividing line at a time, and the Tories have another one that’s been quite prominent in the early days of the campaign, as seen in this Facebook ad spotted by Who Targets Me:

The interesting thing about this dividing line is that, language choices aside, it is undisputed. The Tories say that Labour will stop the planes, because Labour say that they will stop the planes. This is, quite unusually, an actual substantive policy argument. Labour really do think that this is a terrible policy, and they really do want to stop it. Now that we know that there will be no Rwanda flights before the election, we know that if Labour wins there will be no Rwanda flights at all, and the Conservatives are completely within their rights to say so.

The Tories are pushing these ads towards voters who they think back the Rwanda plan, want it to continue and would be disappointed if Labour scrapped it. Those voters are real, but Labour has made two judgements that are quite significant when thinking about how politics might play out after they win, if they win. One is, as I said above, that this is a terrible policy and they don’t want to carry it out. The other is that Labour’s electoral coalition contains a lot more people who want to see the policy scrapped than people who want to see it continued. Once the election is over, the group of people Labour will need to keep happy will be different from the group of people the Tories have needed to keep happy, and different from the group of people Labour has had to persuade to move over. And that means that the politics of the post-election period may have a different shape from the politics we’ve all got used to. It’s time for change.

I am indebted to the excellent Substack Full Disclosure, run by the Who Targets Me project, for tracking and flagging this and other ads which I would otherwise not have seen, as someone who doesn’t really use Facebook any more and might well not get Conservative ads targeted at me even if I did.

At the time, I thought it was an odd moment to launch the dossier - there was no particular hook for it. Why not wait for the start of the election campaign, I thought. Well, now the timing makes a lot more sense.

I worked on the equivalent dossier for Labour in 2010. It doesn’t seem to be online any more, and I can’t find my copy of it, but it was a lot longer - 148 pages versus the 24 of this one - and its impact was somewhat undermined by Patricia Hewitt and Geoff Hoon attempting a coup against Gordon Brown the week we launched it. I have managed to find an online copy of the subsequent 180-page update we did, for the three readers interested enough to click the link. Anyway, without arguing about the precise figures, our basic argument - that the Conservatives would have to drop some of the policies they had announced, make deeper cuts to public spending deeper than the ones they had publicly set out, and raise more taxes than they were committed to raising - turned out to be completely true: they did all of those things. But they did them because we lost the election, so there is a limit to the pleasure I can take in that.

Great article and I look forward to more during the campaign. In 2017 there felt like another dividing line which was Ridiculous figure/Not a Ridiculous figure. As well as the social care U-Turn there was a fields of wheat-based deterioration of Theresa May's image from Iron lady to a bit of a ridiculous figure. At the same time, the image of Corbyn's authentic-ness peaked as he bought a Big Issue in a train station (suggesting he was not a ridiculous figure). There was a similar thing with Neil Kinnock and Ed Miliband not being Prime Ministerial enough. Do you think this will be a dividing line this time?

Likewise, do you think the Lynton Crosby dead cat bounce will be used by the Conservatives this time? Often that helps to make the dividing line clearer.