Jeremy Corbyn became Leader of the Labour Party because of a pledge card. Obviously, that’s not true. But it’s not not true either, and an oversimplified breezy generalisation is a good starting point for an article, so hear me out.

Labour’s “controls on immigration” mug in 2015 is a piece of collateral that came into existence because of the inexorable logic of a process rather than a conscious decision by anyone to create a weird and offensive piece of household crockery. The problem that it was weird and offensive was not immediately obvious to those responsible for it, at different points on the chain of accountability; it became very obvious to most people very quickly, but by then it was too late. And funnily enough another piece of collateral which did Labour enormous damage - the Ed Stone - came out of exactly the same process.1 Pledge cards are dangerous things.

Labour likes pledge cards, because it once won an election with one. Let’s be clear what I mean by “with one”: it didn’t win the 1997 election because it had a pledge card, but it did win the 1997 election, and it did have a pledge card at the time, so it won with one. Pledge cards are easier to copy than many of the other components of the 1997 Labour landslide, so Labour keeps copying them.

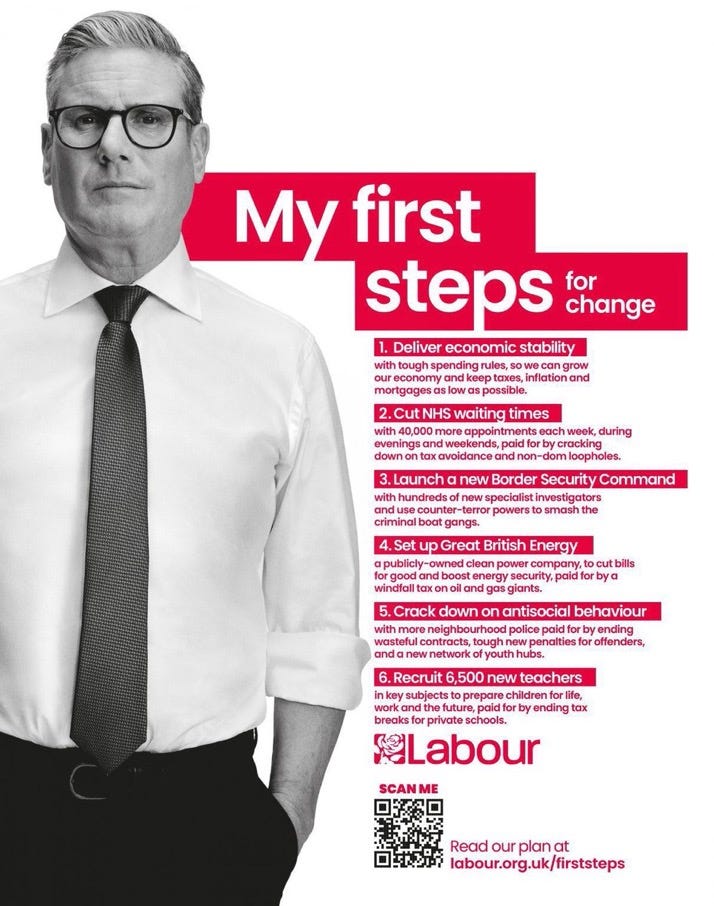

It copied it again last week, with Keir Starmer’s list of “My first steps for change”.2

The point of an exercise like this is to distil a lot of policy across a lot of areas into a small number of comprehensible policies in a small number of areas thought to be considered most important by the voters who most need to be convinced. And indeed, the process of distilling what is inevitably a lot of detail into as few words as possible is a valuable exercise in itself, as a way of working out if your policies are campaign-ready.3

Most of these areas (not policies) will be roughly the same from election to election but they will vary a bit and they will cause different arguments about what’s been left out and why. In this case, for example, Labour’s real commitments to planning reform and changes to employment law have been left off, and I wouldn’t read anything into that about how likely they are to do them, but plenty about Labour’s judgements about their relative importance to target voters.

There’s a longer version with a bit more detail, and it’s hard to get this on a card, so the graphic is bigger.4

Compare and contrast, as they say, with Tony Blair’s 1997 version.

These are much tighter, with the headline of each policy in bold and a brief expansion, including where relevant a costing mechanism, within a single sentence. The longer version of the 2024 list has this detail, but it takes longer over it. The 1997 pledges are also all measurable: Labour could have succeeded or failed on all of them over the course of its first term. The fact that it had asked to be held accountable for them, and could have failed on them, was of course a major driver in government towards making sure that they were all achieved, and we can argue about whether they were the right priorities and whether achieving them got in the way of achieving other, more important things. Love them or hate them, you can’t deny that they are policies.

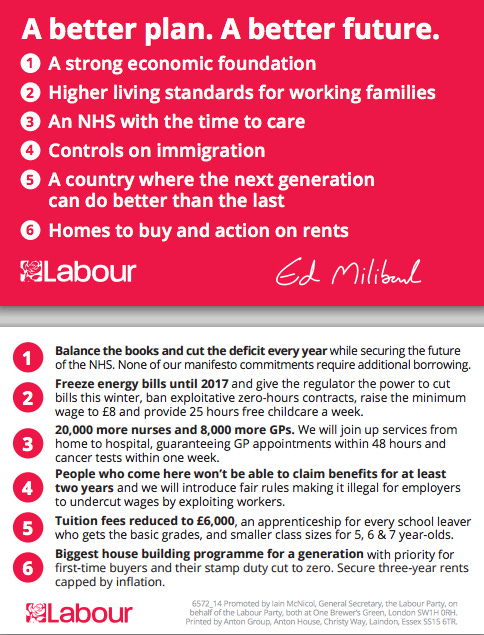

Time for another compare and contrast. Here’s the 2015 pledge card:

The first thing you notice about these is that none of the pledges at the top (the front of the double-sided card) are policies. They are themes. That means that each one covers a wider range of commitments than anything on the 1997 card, but none of them are, in themselves, commitments for which a Labour government could be held accountable. If Labour had won the 2015 election, nobody could have voted for or against them in 2020 on the basis that they had succeeded or failed at creating a country where the next generation can do better than the last. The policies come in at the next level down, or strictly speaking on the other side of the pledge card. These are, in principle, deliverable, but they’re the small print not the headlines. And, famously, it’s the headlines - or, more accurately, one of the headlines - that people remember.

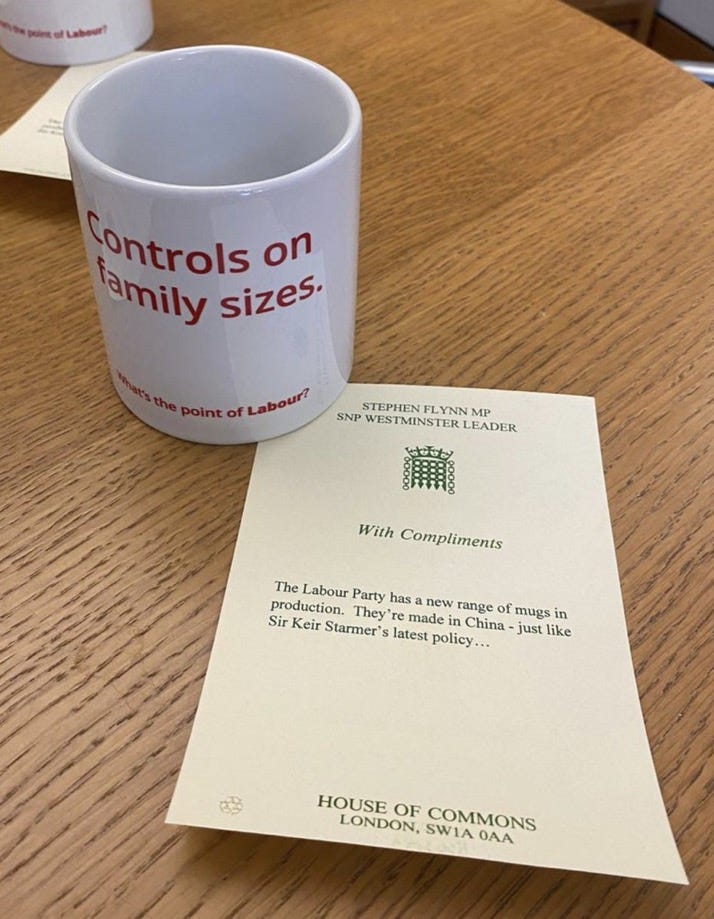

How did “Controls on immigration” get on a mug anyway? Well, because all of the pledges got their own mug, because all of the pledges had got their own mugs in previous elections. Once the text of each pledge had been agreed, nobody thought very hard about whether it was ok to present each one in isolation. Signoff for the whole package meant signoff for the mugs. And there were five mugs. I haven’t got the full set, and I haven’t got an immigration mug. I’ve got an “A strong economic foundation” mug.5 Here it is, just to prove it exists:

Nobody cares about the “A strong economic foundation” mug. They care about the “Controls on immigration mug”, because its existence implies that Labour believed that some people would want a “Controls on immigration” mug. And, to be fair to Labour, some people would, but to be fair to those people, they all want it as a joke.

This is supposed to be a newsletter about political attack, and so far nothing in this post has been about political attack. Well, it is now. Labour’s immigration mug became a useful shorthand for people who wanted to say that Labour had completely lost its way in pandering to the kinds of voters it was never going to win anyway by telling them things it didn’t believe anyway. Here’s a response to it from the Green Party:

And here’s a much more recent response to it from the SNP, taking a completely different policy - the Tories’ two-child benefit cap - and casting it as a Labour policy because Labour has not committed to repeal it:

Labour opened itself up to this. Never give your opponents a short, catchy, easy to understand way of making a compelling political point while ridiculing you at the same time. As I said earlier, it’s not quite true to say that the immigration mug derived from the 2015 pledge card is the reason Jeremy Corbyn won the 2015 Labour leadership election, but it’s a symbol of the broader set of reasons why he did: a party that had so lost touch with its own members that it put policies they hated on a mug.

The tragic secret of the “Controls on immigration” mug is that Labour’s actual policies to control immigration in 2015 weren’t even things the left-of-centre voters and Labour members repelled and embarrassed by the mug would have hated, but they were quite deliberately made to sound harsher than they really were by being put under a “Controls on immigration” heading. The main ones were about making it harder for unscrupulous employers to exploit immigrant workers by paying less than the minimum wage, which nobody on the left disagrees with: these are immigration controls, but they’re not what anyone thinks of when they hear someone calling for immigration controls. The headline policy on the pledge card, about stopping people who come here claiming benefits for at least two years, sounds vaguely tough, but it only has an impact if people actually come to the UK to claim benefits, which by and large they don’t anyway. None of that is to defend the pledge, or the mug, or the messaging. People who liked the slogan didn’t believe Labour would control immigration, and people who didn’t mind the policies hated the slogan.

I am pretty sure that the “first steps” launched by Keir Starmer last week will not be put on mugs.6 But they are designed to be broken up and used in isolation as well as together on one card. I noticed a Labour PPC tweeting each of them separately, including the one on immigration:

This is the direct equivalent of the “Controls on immigration” pledge, and it’s… fine. It’s tightly focused on a particular element of the immigration debate which people care about - small boats - without being phrased in a way that suggests immigration is a problem more broadly. It would be a bit weird to put it on a mug, but it wouldn’t be a political disaster.

Meanwhile, the Ed Stone - perhaps the single most ridiculed piece of political communication in my lifetime - was essentially a giant pledge card, carved at great expense into a massive piece of limestone.

It was launched in Hastings on the final weekend of the campaign, and by coincidence I went to Hastings a couple of days later to help knock on doors (Labour HQ staffers are generally sent out to marginal seats in the final days of elections because there are fewer and fewer things to do in the office). One of the Labour members I met there had attended the launch and had stood only a few feet away from the stone although - as it soon became clear - not quite close enough to touch it. We already knew, by the time we were chatting to each other on a sunny doorstep round, that the whole thing was a disaster and a laughing stock. She put a brave face on it. “Oh well”, she said. “At least it wasn’t a real stone”.

One of the strange things about being an ex-political adviser is that your former job is interesting enough for people to be interested in it, controversial enough that people want to attack you for having had it, and vague enough that people can make assumptions and project things onto it that may or may not be true. This creates misapprehensions and incentives for political opponents and random people on Twitter about what to claim about ex-advisers and what to accuse them of, and dilemmas for ex-advisers about what to disavow and what to defend. I tend to let it slide when people who don’t know me try to pin specific bad things from my time working for Labour on me. There is a kind of collective responsibility on everyone who played a role in a losing election campaign (or, in my case, three) and it feels ungallant to try to wriggle out of responsibility for something just because, strictly speaking, it was nothing to do with me. Nevertheless, for the record, I had no direct involvement with the following disasters, along with a few others I’ve probably forgotten about: the Blackbusters tweet, the bacon sandwich, the accidental owl pledge, the immigration mug and the Ed Stone. If you want to attack me for them anyway, that’s fine, knock yourself out. But it’s worth bearing in mind that I didn’t do them, I already know about them and I didn’t think they were good even at the time.

The Tories described this as “Keir Starmer’s 16th relaunch”.

Earlier the same week, Labour described Rishi Sunak’s speech at Policy Exchange as his “seventh reset in 18 months”. These are both examples of a very standard, and very boring, attack move: it is impossible to make a big, general pitch to the electorate without the other side describing it as a relaunch. I know why they do this but I wish they wouldn’t.

My former Labour colleague Karim Palant made this point the other day and I agree with everything he said here but I note that he was - ironically - unable to distil his point down enough to get it into one tweet.

To be fair, there is a version of this without the Starmer photo that does get it onto one card, but I couldn’t find a good picture of it. And to be even more fair, in 1997 people weren’t all walking around with hand-held devices which enabled political communications material to be presented in unlimited formats: pledge cards don’t have to be cards any more. But still, brevity is good.

I think I nicked it. There wasn’t a crime pledge.

I realised when I was writing this that I am not 100% sure. But I hope I’m right. Mugs are so over.

I do find it interesting the way they recycle the idea of a pledge card without actually emulating the core point: that they were very specific, measurable pledges.

I think the person who came closest to emulating the 1997 pledges (though I can't remember if they were put on a card, let alone mugs) was Boris in 2019, with Get Brexit Done, 20,000 new police officers, more money for the NHS, more money for every pupil in school and an Australian points based immigration system. As in 1997, you can debate whether they're the right ones (the focus on pounds spent in 2/5 was non ideal in my book) buy they were all specific and somewhat memorable.

On mugs, my best mug story is I have a Brexit mug with the wrong date on it (31 October 2019), produced in a fit of over-optimism by the Business Department.

I still refuse to believe that the Ed Stone was actually real. Even at the time it seemed like a bad joke, and the more time passes the more it seems like some kind of weird demented dream.

And very few people can say they ever actually saw it…