Consider a major public policy issue that has been unresolved for years. It affects some of the most vulnerable people in the country. Everyone agrees that it’s important, even if they disagree on the solutions. Everyone agrees that long-term policy failures over decades have caused - and continue to cause - real suffering. There have been a series of inquiries over recent years, and a set of policy recommendations that have - for the most part - not yet been implemented. Now is the time for action, not for another review into adult social care, as this Times leading article from last week says.

Meanwhile, consider a major public policy issue that has been unresolved for years. It affects some of the most vulnerable people in the country. Everyone agrees that it’s important, even if they disagree on the solutions. Everyone agrees that long-term policy failures over decades have caused - and continue to cause - real suffering. There have been a series of inquiries over recent years, and a set of policy recommendations that have - for the most part - not yet been implemented. Now is not the time for action, it’s the time for an inquiry into child sexual abuse by grooming gangs, as this Times leading article from last week says.

It isn’t just the Times calling for a national inquiry into grooming gangs. It’s also the Conservative Party. There are a number of reasons why they have done this, and one of them is that well-known Donald Trump, Liz Truss and Tommy Robinson (but not Nigel Farage) supporter Elon Musk has started tweeting about the issue, but another is that calling for inquiries is, for opposition parties, safe ground.

Kemi Badenoch won the leadership on a platform of taking time to set policy. This is, as I wrote just before the leadership election result, sensible: the Conservatives have time, their rejection by the electorate means that they have to change at least some of their policies, their next manifesto will need to be about the world as it is in 2029, and they don’t need to write it now.

You can overdo this. Ed Miliband said in an interview early in his leadership of the Labour Party that “In terms of policy, but not in terms of values, we start with a blank page”. This quickly - and predictably - became an attack line for the Conservatives and Lib Dems. Badenoch’s three-year timetable, as reported by the Sun’s Harry Cole, carries similar risks.

There is a nice symmetry between the Tories’ repeated attacks on Miliband’s “blank sheet of paper” and Labour’s line this week that the Tories are “offering an out of office reply for the next two years”. Having policies is risky, and not having them is risky too.1

There are ways around this. One is to use the standard “if we were in government now” gambit, where oppositions set out things they would be doing in the current context, or call on the Government to implement particular policies today (the “here are five things that the Chancellor should include in the Budget next week” call), without committing to including them in their next manifesto or pre-empting whatever policy review process is going on. Another very tempting one, when a policy issue becomes topical and when, with the best will in the world, there is no way an opposition party is going to take a strong position on it now, is to call for an inquiry.

This is where Badenoch’s Conservative Party is now on a grooming gangs inquiry, and the parallels with Miliband’s Labour leadership are pretty obvious - Rob Hutton picked up on this in his sketch on Tuesday. During that period Labour called for independent inquiries into the banks, PIP breast implants, care home abuse, cash for access, the 2011 riots (this one happened2), GCSE English papers, the West Coast Mainline, phone hacking (this one happened, in the form of the Leveson Inquiry), the culture and practices of the Daily Mail (this was separate from the call for what became the Leveson Inquiry) and the Jimmy Savile scandal, and probably more. Individually, each of these calls was not without merit, although some had more merit than others. Cumulatively, the appearance of a default “call for an inquiry” response to any complex policy problem became a problem in itself.

Calling for an inquiry is a signal that you think something is important which puts the Government into an awkward position - they have to either agree to an inquiry, which means you can say they’re dancing to your tune, or reject one, which means you can say they must have something to hide - but avoids committing to any particular policy on it now.

The Tories have gone in very hard in calling for a grooming gangs inquiry, despite the fact that having both rejected such an inquiry in government and failed to implement the recommendations of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, they are on somewhat shaky ground on the issue: they have no real explanation for why they didn’t think of this one before, apart from the real explanation that it is in the news.3

One of their tactics this week was that other classic opposition move: “forcing a vote” on something. In this case, they forced a vote in a slightly bizarre way, by asking MPs to reject the entire Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill and hold an inquiry into grooming gangs instead. It is not an inherently unreasonable position to want an inquiry into grooming gangs, but to want one instead of a piece of legislation about a whole range of other things including some child safeguarding measures makes very little sense. Similarly, it is perfectly reasonable for the Conservatives to oppose the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill - and they do have a series of objections to it which, whatever your views might be, do relate to the substance of the Government’s proposals - but opposing it on the grounds that it is not a grooming gangs inquiry is bananas.

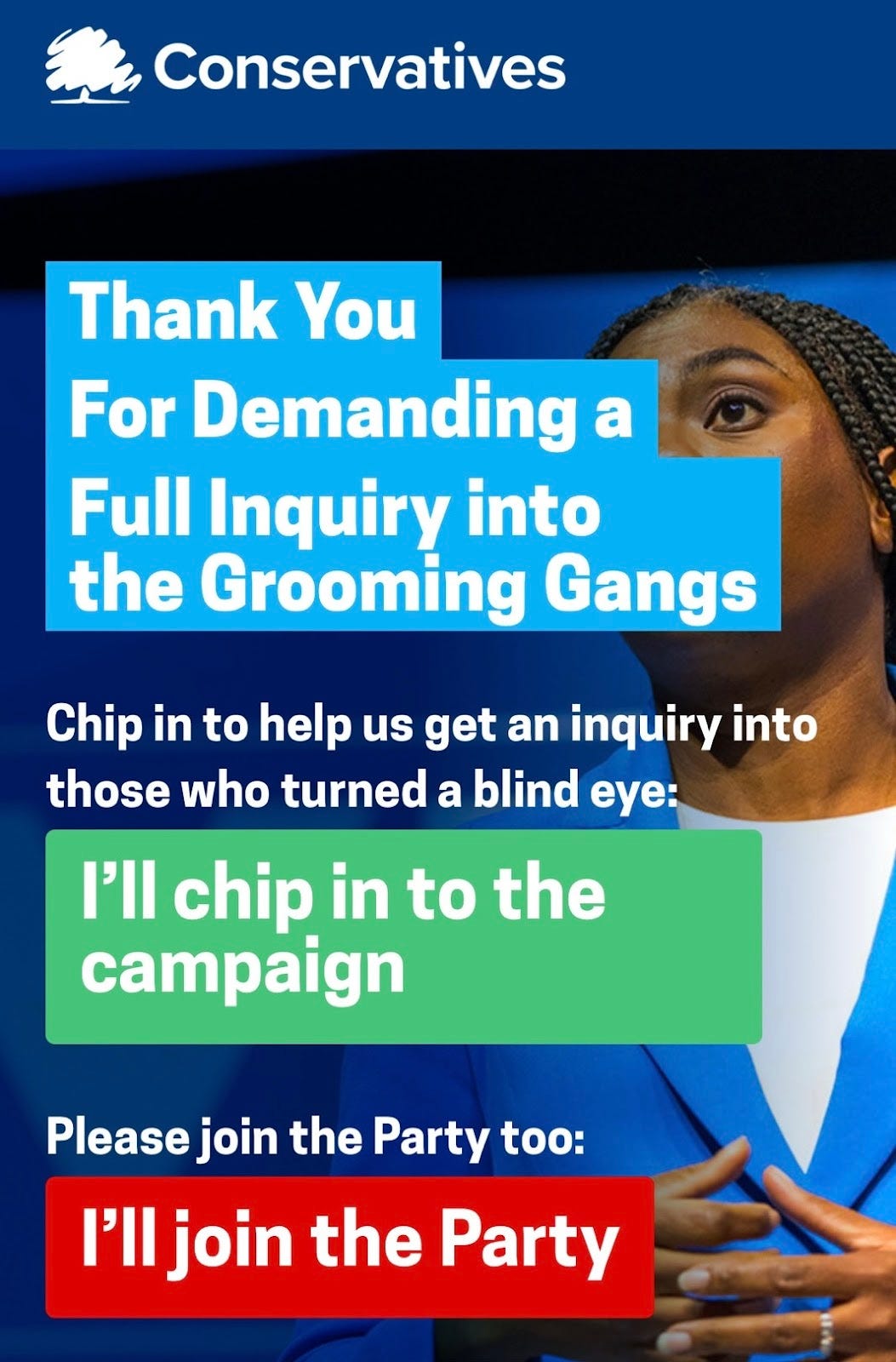

Still, they pushed the issue, lost as expected, and (as pointed out on Bluesky by Adam Bienkov) attempted to fundraise off the back of it. It is, as they say, an ill wind that blows nobody any good.

One aspect of the debate which appears to have particularly annoyed the Conservatives, sincerely or otherwise, is Keir Starmer’s characterisation of their position as “jump[ing] on a bandwagon of the far right”. Here’s the resulting Telegraph front page.

It’s worth spending a bit of time on this because it involves a rhetorical move that’s quite common, easy to spot if you’re following in detail, and hard to spot if you only come in once the argument has moved to “Keir Starmer says that if you care about grooming gangs you’re far right, that’s outrageous” and “Is it far right to be concerned about grooming gangs, yes/no?”.

This is a long quote from the Q&A after Keir Starmer’s speech on Monday, and it’s long because it’s an argument:4

Those that are spreading lies and misinformation as far and as wide as possible, they’re not interested in victims. They’re interested in themselves.

Those who are cheerleading Tommy Robinson are not interested in justice. They’re supporting a man who went to prison for nearly collapsing a grooming case, a gang grooming case. These are people are trying to get some kind of vicarious thrill from street violence that people like Tommy Robinson promote.

And those attacking Jess Phillips, who I’m proud to call a colleague and a friend on protecting victims - Jess Phillips has done 1,000 times more than they’ve even dreamt about when it comes to protecting victims of sexual abuse throughout her entire career …

We’ve seen this playbook many times, whipping up of intimidation and threats of violence, hoping that the media will amplify it.

Jess Phillips does not need me or anybody else to speak on her behalf. But when the poison of the far right leads to serious threats to Jess Phillips and others, that in my book [means] a line has been crossed.

I enjoy the cut and thrust of politics, the robust debate that we must have, but that’s got to be based on facts and truth, not on lies, not on those who are so desperate for attention that they’re prepared to debase themselves and their country.

So this government will get on with the job of protecting victims, including child sexual abuse, mandatory reporting, accelerating the processes.

But what I won’t tolerate is this discussion based on lies without calling it out. What I won’t tolerate is politicians jumping on the bandwagon simply to get attention when those politicians sat in government for 14 long years, tweeting, talking, but not doing anything about it – now so desperate for attention that they’re amplifying what the far right is saying.

So that’s what I say about Jess Phillips, Thank you.

Starmer said something similar a bit later, with a slightly closer link between the words “bandwagon” and “far right”.

And when politicians, and I mean politicians who sat in government for many years, are casual about honesty, decency, truth and the rule of law, calling for inquiries because they want to jump on a bandwagon of the far right, that affects politics because a robust debate can only be based on the true facts.

Here’s how the argument goes. There are lies and misinformation being spread by Tommy Robinson and his supporters, and by others who can reasonably be identified as being on the far right (this includes, in this context, Elon Musk who has explicitly backed Robinson and his claims).5 Tommy Robinson is not someone mainstream politicians should be supporting or amplifying. Jess Phillips is committed to tackling sexual violence and has a strong track record of doing this, and some on the far right are lying about her. Misinformation has led directly to threats to Jess Phillips’ safety. For mainstream politicians to join in the debate without distancing themselves from the far right misinformation some in the debate are spreading is bad, because honesty, decency, truth and the rule of law are values that everyone should want to preserve whichever side of the argument they are on. Calling for an inquiry is not far right. Being concerned about grooming gangs is not far right. But coming into a debate where the far right are active without drawing clear lines is dangerous, because it amplifies and emboldens the far right and puts people like Jess Phillips at risk (while, to be clear, not being far right in itself).

You can make the case that this argument is one Starmer should not have made because, while it is in my view correct, it is vulnerable to deliberate or accidental misinterpretation. Here’s Conservative MP and former Home Secretary James Cleverly deliberately or accidentally misinterpreting it.

You can see the move Cleverly is making here. Starmer is not saying that people who disagree with him or seek legitimate answers about repeated failures of child protection are “far right”, and Cleverly will know this if he has listened.6 He is calling for clear lines, and an upholding of basic standards of decency and truth in a debate where some have no regard for them, so that those who are not on the far right and are concerned about this remain distinct from those who are on the far right and just lie. The same move is made in this Conservative graphic.7

Again. It is not far right to want justice for the victims of rape gangs, as witnessed by the fact that some of the people who worked to get justice for the victims of rape gangs, not least the actual Prime Minister, are now senior members of the Government. But, uncontroversially, some people who want justice for the victims of rape gangs are on the far right. For example, here is Elon Musk’s response to Starmer’s comments.

This is deranged. It is a far right position. It should not be difficult for the Conservatives to say so even while continuing to call for an inquiry.

Political projects need boundaries: they need to show who they are not for and who they do not stand with, as well as who they are for. Nigel Farage’s decision to maintain a distance from Tommy Robinson, even at the cost of Elon Musk’s support, shows that he understands this. Keir Starmer’s leadership of the Labour Party, particularly in its early stages, involved the drawing of some quite clear boundaries between his project and the previous leadership. Kemi Badenoch has so far not shown a willingness to make important distinctions between her leadership project and other parts of the right which she would be well-advised to distance herself from (and which, to be fair, I am sure she despises), despite choosing to campaign hard on an issue that gives her a perfect opportunity to do this. Calling for an inquiry is not the problem. How she’s called for it is.

It is worth saying that it is already not quite true to say that the Conservatives have no policies. They have committed to reversing Labour’s inheritance tax changes for farmers and removing Labour’s imposition of VAT on private schools. As I wrote previously, both of these are spending commitments whose main appeal is to the core Conservative vote, which makes them interesting signals.

This is nothing to do with the riots inquiry, which is why it’s a footnote, but I defy you to find a more unintentionally hilarious opening line than the first sentence of David Cameron’s riots speech, delivered following an outbreak of unrest and looting in cities around the country: “It is time for our country to take stock.”

The fact that it is in the news is not, by the way, a bad reason to want to talk about it now. But it is not a good answer to the question “Why didn’t you do more about this before?”

And also because this is Substack and I am not subject to a word limit.

I highly recommend this piece by BBC Verify on one particular piece of misinformation.

There’s an element of self-incrimination in choosing to insert yourself unprovoked into “Liars are far right” / “How dare you say I’m far right?”

The graphic is based on a Labour graphic from 2023 which I wrote about here. I said then that I thought the ad was something I wouldn’t have wanted to do because it was more trouble than it was worth, but that it was defensible, and this is still my position. I think parodying it is fine, and that the Tory ad is absolutely defensible, apart from the “Keir Starmer thinks you are far-right if you want justice for the victims of rape gangs” bit, which is unambiguously a lie.