Waiting for a winner

If you’re a committed supporter of a political party, the other side’s leadership elections can mess with your head. You want them to lose, which means you want them to pick the most unappealing candidate. But the most unappealing candidate is the one you like least, and wanting them to win something - anything at all - feels wrong. And while you have to assume that picking an unappealing candidate makes it harder for the party you dislike to win a general election, you can never fully discount the possibility: the worst available leader of the opposition could, if everything goes wrong, become the worst available prime minister. The Tories laughed when Labour chose Jeremy Corbyn. Then they stopped laughing.1

The fact that in any leadership election there can only be one winner adds another element of confusion. Everyone who gets knocked out of the other side’s leadership contest is someone you want to lose elections. The current Tory contest, in which a large number of candidates were whittled down over several weeks to a final two, has provided us with the biggest parade of defeated Tories since, ooh, July. That feels fun until you remember that there’s still going to be a winner in the end, and the winner is still going to be a Tory.

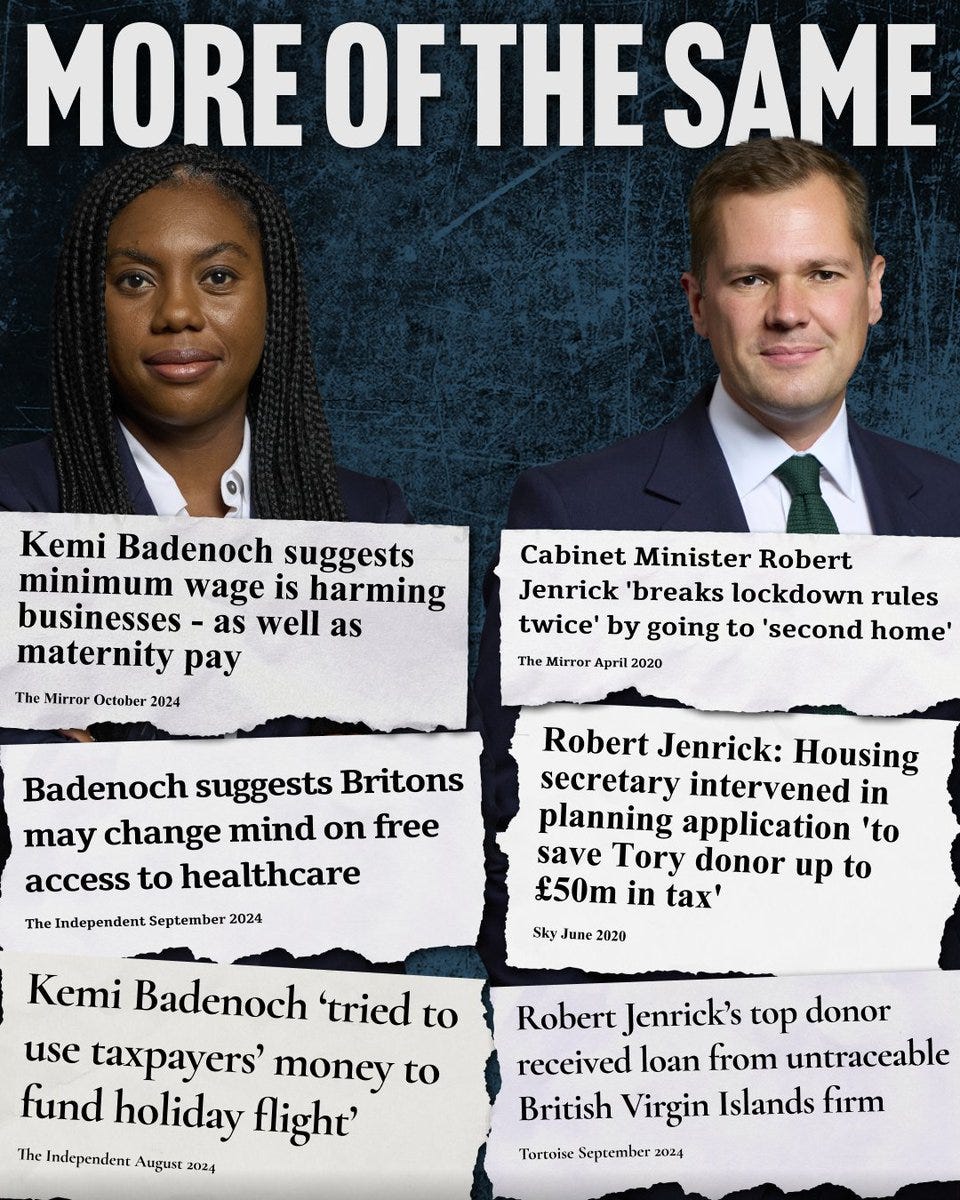

Both Kemi Badenoch and Robert Jenrick have weaknesses, and while it would be unwise for Labour to be complacent, I tend to agree with the conventional wisdom that they are not the candidates Labour would or should have feared most.2 Here’s Labour’s pre-result attack on the pair of them.

I also agree with the conventional wisdom that Badenoch is, of the final two, the better option for the Conservatives to take.

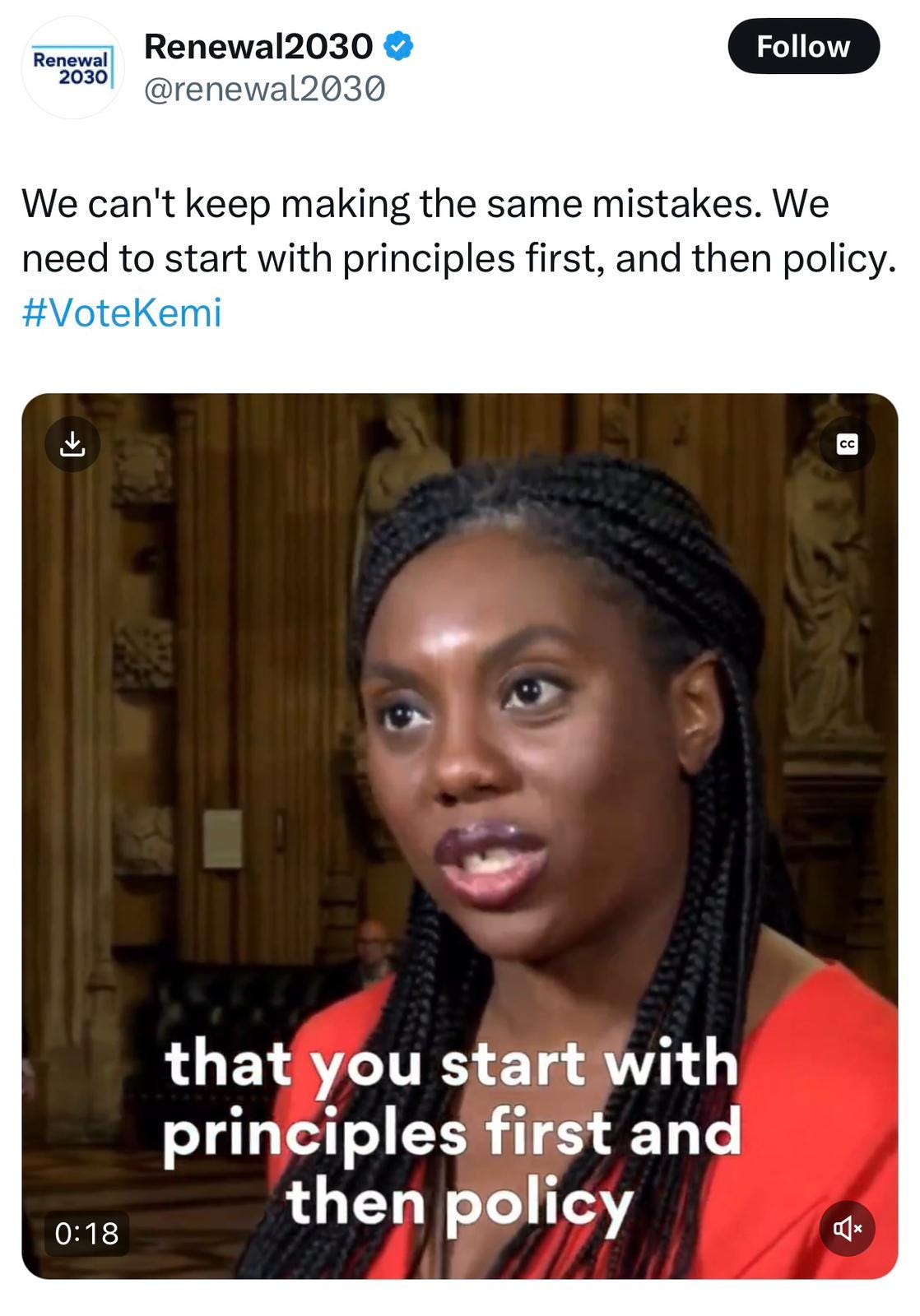

Part of that is because of where she stands on what has turned out to be one of the biggest dividing lines of the Tory leadership race, the question of whether the party needs a detailed plan straight away. Badenoch has argued for a focus on principles, with policies coming later.

You can overdo not having any policies. For example, the Tories ought ideally to elect a leader who has not said she might change her mind in future on whether the NHS should be free at the point of use, given that the public - however frustrating this may be to some newspaper columnists - shows no signs of doing so. And they ought ideally to elect a leader who is able to avoid being ambiguous about whether maternity pay is an example of a regulation that has “gone too far”. That derives directly from wanting to have a principled position that is all principle (there is too much regulation) and no policy at all (let’s not talk about which regulations we mean). This stuff isn’t hard, and the fact that Badenoch has made it look hard should worry her supporters.

Jenrick, meanwhile, believes that the Tories simply don’t have time to waste having policy debates:

It is probably worth pointing out that although Jenrick has set out some policies - notably his desire to leave the ECHR which, as Danny Finkelstein points out, is opposed by a substantial chunk of the parliamentary Conservative Party and would therefore make it harder for him to populate a front bench team - his platform overall is surprisingly difficult to track down for someone who says he has one.3 But for the sake of argument, let’s accept that Jenrick has a plan. The problem is that if that’s true, it shouldn’t be. The Conservatives don’t need a plan now.

To lead the Conservative Party into the next general election - not to win the next election, but just to be in post when it happens - Jenrick or Badenoch will have to be the longest-serving Tory leader since David Cameron. That’s partly a sign of just how many leaders the Tories have managed to get through in the last eight years. But it’s also a reminder that for the time being, they don’t need to be in a hurry. There isn’t going to be a general election in 2025. Or in 2026. Or in 2027. Slow down.4

Jenrick appears not to have noticed how much time he has. That’s a problem. But he also appears not to have noticed something else that’s absolutely crucial for oppositions to spot: oppositions and governments are not the same thing.

Have you spotted the problem here? It is possible that the Conservatives in opposition can end the drama. It is possible that they can end the excuses. They cannot - this isn’t a party political attack, it’s just a description of how the world works - deliver on migration.5

It’s a cliché that the difference between government and opposition is that in government you can do things, but in opposition you can only say things. It’s a cliché, though, because it’s true.

The conceptual mistake of thinking that you are not irrelevant is common to opposition parties, because being irrelevant is never fun, and the least painful way of dealing with it is denial. Anyone who has worked for, or been an active member of, an opposition party knows what this looks like. Which brings us to Breaking Blue, a recent report by the right-of-centre think tank Onward on why the Conservatives lost the 2024 election and how they can get back into office

“The Conservatives”, Onward tells us, “suffered as a result of anti-incumbency arising from the events of the last 2019-2024 Parliament”. The term “anti-incumbency” sounds like a force of nature that just happened to hit the Conservative Party at an unfortunate time.

Onward’s subheadings in the chapter unpacking it, all of which are more than fair, make it clear that it was not just, you know, one of those things. “Support for the Government over Covid and vaccines evaporated over ‘Partygate’”; “Dissatisfaction with Boris Johnson harmed the party”; “Incompetence and lack of delivery”; “Voters blamed the Government for ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ performance in key areas”; “2019 Conservative voters rated key policy areas negatively and blamed the Government”; “Conservatives were seen to have broken their promises on immigration and the NHS”; “The 2022 ‘mini budget’ damaged perceptions of economic competence”. Lads, I’m sorry. This isn’t anti-incumbency. It’s anti-you.

Onward identifies the main barriers to supporting the Conservatives among those who voted for the party in 2019 but not in 2024, in descending order of priority: immigration is too high, the party is weak and divided, and public services have got worse.

One of these things is not like the others.

The Conservatives could conceivably become less weak and divided between now and the next election, although this is easier said than done. But they can do nothing to cut immigration or to improve public services. Nothing. This is because they are not the Government. It is also why they are not the Government.

That means that if taken literally, Onward’s report is a counsel of despair. “When asked what the Conservative party needs to do to make them more likely to vote for it again, reducing immigration was the top priority among all 2019 defector groups”, it says. Well, the Tories can’t reduce immigration. Not before the next election. Tough.

The Conservative Party can promise to reduce immigration and improve public services, and it can put forward policies designed to do so. But they will be heard by the public - if the public are listening at all, which is a whole other problem - in the context of a broad perception that these are things the Tories are rubbish at, and can’t be trusted on. You can accuse the Conservatives of many things on immigration, but not that they neglected to tell people they wanted it to go down.

Now, it is possible that this is just imprecise drafting, rather than a fundamental conceptual error. But either way, it reflects a problem all defeated parties face. The things the public most want you to sort out are the things you did worst on in office. And the fact that you did so badly on them in office means that they are the issues on which your credibility is lowest.

And that in turn means that having policies that people like is not the same as having the ability to persuade people to vote for you. It is easy to forget that most parties, in most elections, have policies that people like. Yet most parties, in most elections, lose.

It takes a long time for the public perception of competent party management, if such a thing can be achieved, to overcome the public perception of its incompetent actual record in government. Credibility is based on the past, not just the present. That helps to explain why multi-term governments are so common, and single-term oppositions are so rare.6

The first hundred-and-however-many days of the Labour Government have not been an unalloyed success, to put it mildly. They have made mistakes, and they have done things that are unpopular. That has made some Conservatives optimistic. There are certainly reasons why a second Labour term is very far from inevitable, and reasons why the Conservatives could get back in.

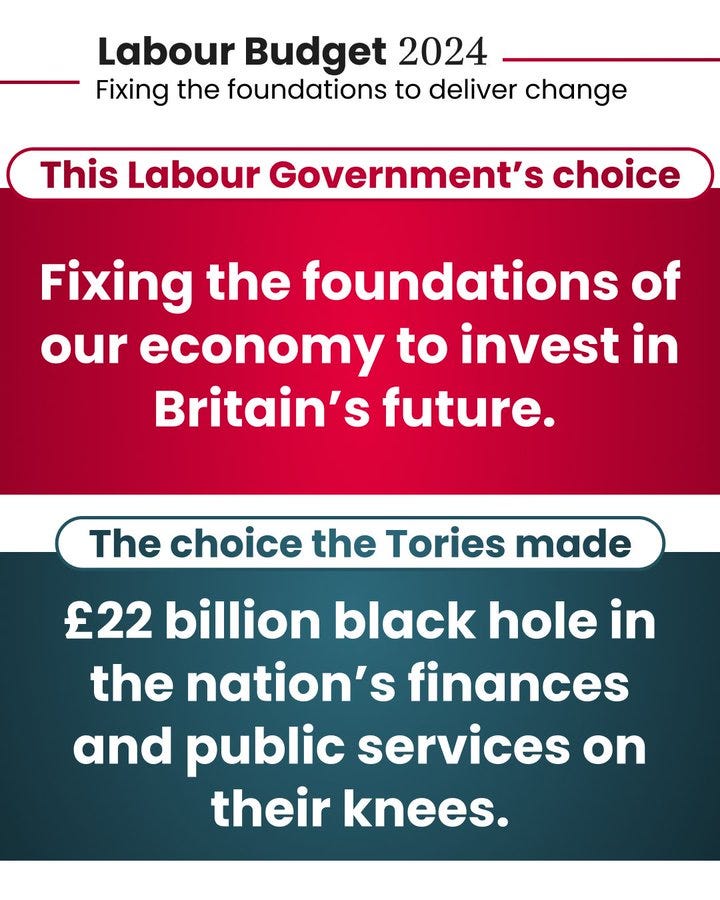

But Onward’s report helps to explain - partly deliberately, and partly perhaps by accident - why it isn’t easy. Robert Jenrick’s assertion that the Conservatives can “deliver on migration” before winning helps to show that not everyone has worked it out yet. And this week’s Budget, whether you love it or loathe it, helps to set out the task the Conservatives actually face in developing their policies over the next four years, rather than the one they would like to face. Rachel Reeves set it out at the end of her Budget speech:

The choices I have made today are the right choices for our country—to restore stability to our public finances, to protect working people, to fix our NHS and to rebuild Britain. That does not mean these choices are easy, but they are responsible. If the Conservatives disagree with the choices that I have made, they must answer: what choices would they make? Would they again choose the path of irresponsibility—the path taken by Liz Truss—and ignore the problems in our public finances all together? If that is their choice, they should say so. But let me be clear: if they disagree with my choices on tax, they would not be able to protect working people. If they disagree with our plans to fund public services, they would have to cut schools and hospitals. If they disagree with our investment rule, they would have to delay or cancel thousands of projects that drive growth across our country.

The Conservative leadership election has not been about these questions. It has been, as all leadership elections are, about the questions the party is interested in and that the party wants to answer. But the new Conservative leader is going to have to answer them, whether they like it or not.

Dividing lines, eh? Annoying, aren’t they? Clunk.

I am well aware that this is my first post for weeks and weeks and weeks. There are various reasons for this, none of which I propose to go into at this time (apart from, I’m not dying or anything, don’t worry, that’s not what I mean at all) but the fact that this post exists should act as some reassurance that this Substack is still a going concern. I did say after the election that I expected posts to be more sporadic than they had been, and I’m proud to be following through on that commitment. One of the reasons Dividing Lines is free is to stop me feeling guilty about only posting when I have something to say.

On the topic of having something to say, I wrote another thing about the Budget, which you can read on LinkedIn here.

Then they started laughing again. This is an important fact, but it’s part of a different argument, and also it’s about time we had a footnote.

I’m always amused by “I am the candidate Labour fears most” arguments, because by definition they are made by people who think Labour is wrong. Logically, they should be followed by “So vote for my opponent”.

It’s not impossible to piece together, but… it’s not as easy as it could be.

I wrote about the challenges facing opposition leaders, and the perils of having too many policies, just before Keir Starmer was elected Leader of the Labour Party, in a piece I think has held up ok.

Robert Jenrick, of course, couldn’t deliver on migration even while serving as immigration minister.

The last person to lead any UK party from opposition to government who had served as a minister in their party’s previous period in government was Margaret Thatcher. The last person to lead any UK party from opposition to government who had been an MP in their party’s previous period in government was Margaret Thatcher. The last person to lead any UK party from opposition to government who had been an MP in their party’s first term in opposition after leaving government was Margaret Thatcher.

Footnote 6 is really striking. Not sure how much relevance it has in an era where so many leading politicians simply don't hang around any more on leaving office, but it's still a sobering stat.

Such a necessary point about not needing a fully detailed policy platform at this stage. The election won’t be held on the challenges of 2024. In four or five years’ time, the broad themes may be the same, and we need to understand a leader’s philosophical stance, but the circumstances will be totally different.