If there’s one thing the Conservatives want you to think about Labour, it’s that they are a risk the country can’t afford to take. This is fair enough: all incumbent governments want to persuade the public that, even if they have some faults, it is safer to stick with them than to change, and that means pointing out all the ways in which their opponents are risky. And so all oppositions want to reassure the public that changing government is safe, and that they can be trusted with the things the public cares about: national security, the public finances, public services.

Labour has devoted a huge amount of time and effort to reassuring the public that they can be trusted (especially on national security and the public finances; Labour never has as big a reassurance job to do on public services). It’s fair to say that this bit of Labour’s electoral project is quite boring, and it’s frustrating to activists and supporters for at least two reasons: as activists and supporters they’re already persuaded and don’t need to be reassured, and as activists and supporters they’re most excited about the kinds of radical policies that tend to get toned down or not talked about or never announced at all in order to reassure voters that Labour is safe. Well, tough: if you’re an activist or a supporter this bit of the project is not about you. It’s about people who haven’t decided who to vote for yet, or who think they’ll probably vote Labour but need reassuring.

So far as the public finances are concerned, Labour’s reassurance project is all about centering Rachel Reeves’ iron discipline, tough fiscal rules and insistence that she will spend public money wisely. And the Tories’ risk-heightening project is all about arguing that actually Labour won’t be disciplined at all: that they will wreck the economy and put your family finances at risk. That’s what interventions like this one are all about:

Sir Keir Starmer would pile £2,200 a year on working families, a Cabinet Minister has claimed – as he challenged the Labour leader to come clean about his spending plans.

Tory Chairman Richard Holden said that Labour’s promise to invest £28 billion in green jobs would be ‘impossible’ without a massive income-tax rise for all workers.

In a fiery interview with The Mail on Sunday, Mr Holden said the pledge, combined with Labour’s vow not to increase borrowing, would lead to the basic rate of income tax rising from 20 per cent to 25 per cent – the equivalent of an annual £2,200 hike for the average two-income household, but Labour strongly denied the claim.

There are at least four things wrong with this. One is that Labour’s fiscal rules explicitly allow borrowing for investment (this is a separate question from whether Labour’s fiscal rules are sensible, or whether the £28 billion pledge is sensible, or whether some people inside the Labour Party are nervous about it, or whether Labour may end up dropping or reducing the level of the £28 billion pledge anyway1 - the point is that unlike pledges about day-to-day spending, Labour’s own rules do not require it to be covered by equivalent tax rises, which is why Labour hasn’t announced any).

A second is that it fails the political common sense test. Will Labour raise the basic rate of income tax from 20 per cent to 25 per cent, hiking the average two-income household’s tax bill by £2,200, in order to pay for its green spending pledge? No, of course it won’t, because the politics of doing so would obviously be completely catastrophic. If you are claiming that Labour cannot do something without raising income tax by 5 per cent, you are claiming that Labour cannot do something. But the problem with making the argument in those terms is that it doesn’t make Labour sound very risky, it makes Labour sound very boring.

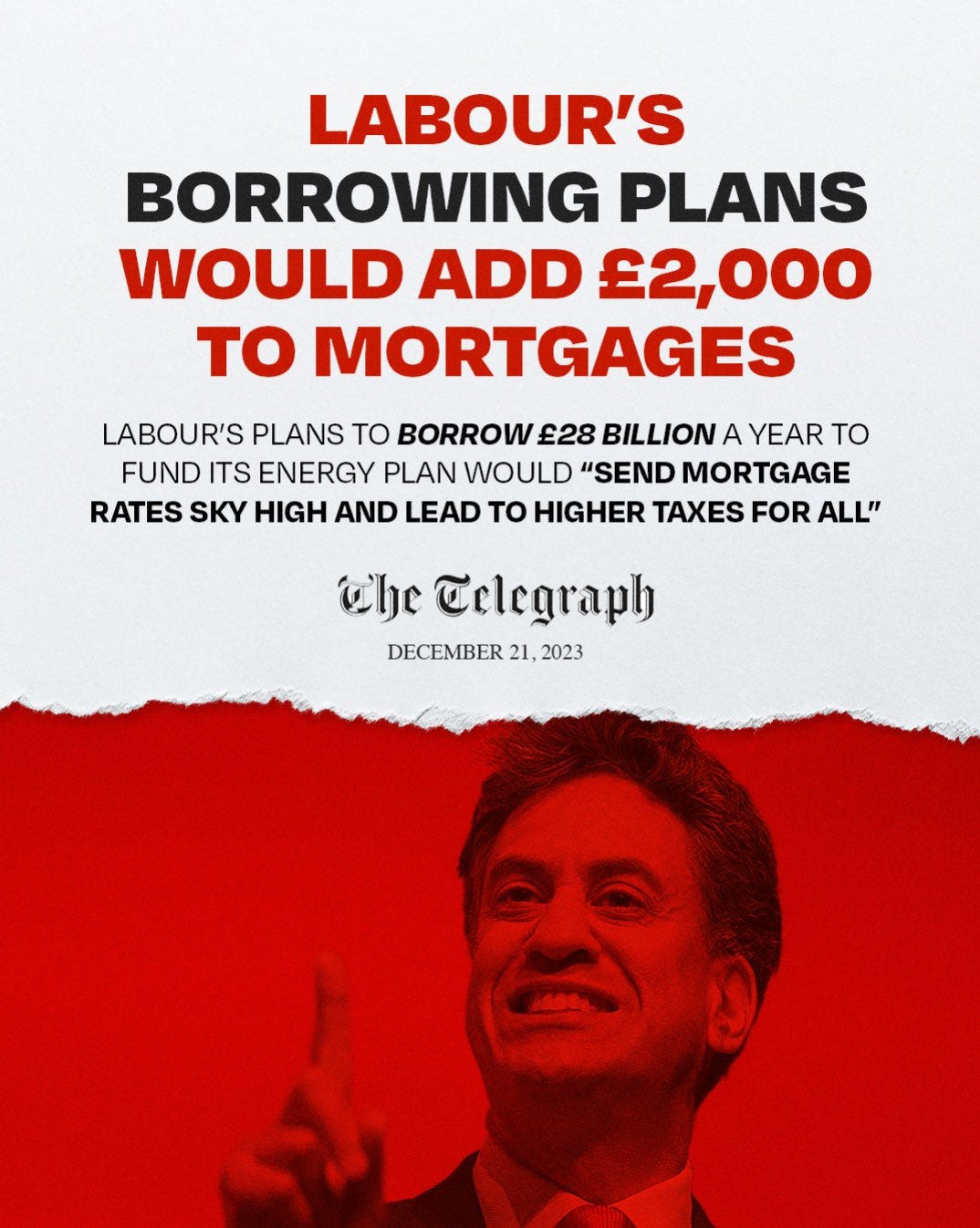

A third is that it contradicts another attack the Conservatives are trying to make at the same time: that Labour’s £28 billion plan is funded by borrowing, not by taxation, and that that is what makes it risky. This is the basis of a graphic tweeted by Energy Secretary Claire Coutinho:

This is based on a Treasury calculation (read: a Conservative calculation):

The department calculates that for every extra 1 per cent GDP of borrowing – equivalent to £25 billion – interest rates could rise by as much as 1.25 per cent, inflicting extra costs on homeowners.

A £200,000 mortgage on a 30-year term would cost £1,920 more a year as a result of the increase, according to a Treasury source.

The source said: “The cat is well and truly out of the bag. Labour’s reckless £28 billion plan will not only ratchet up debt and send mortgage rates sky high, but will invariably lead to higher taxes for all.

“Be in no doubt that working families will pay the price of Labour’s inflationary borrowing binge.

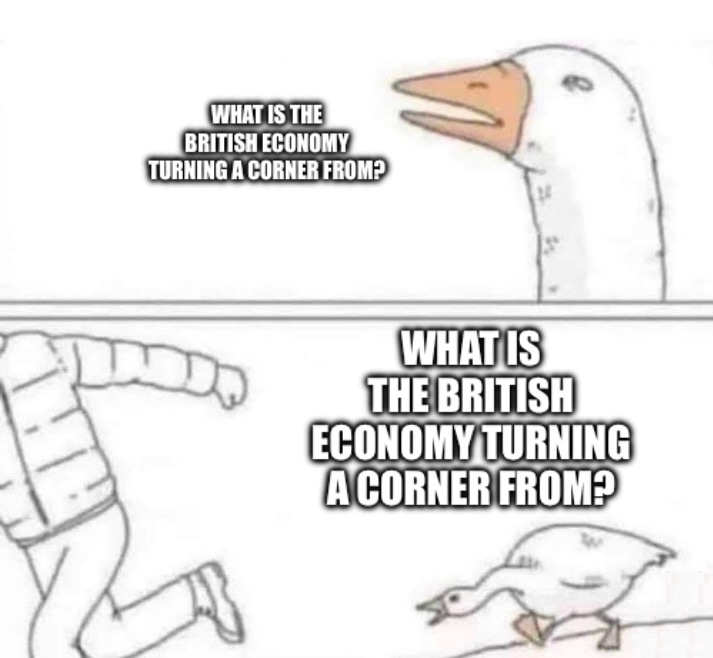

“The British economy is turning a corner with inflation at its lowest level in two years, so don’t let Labour ruin it.”2

At least the Tories in the Treasury seem to have read Labour’s fiscal rules: they should tell Richard Holden, and encourage him to stop briefing the Mail that Labour won’t borrow.

But “Labour’s irresponsible borrowing plans will make your mortgage more expensive”, which would usually be a pretty potent line, is what takes us to the fourth, and biggest, problem with the whole claim that Labour is a risk to the economy. For “stability versus chaos” to work as a contrast, you have to own stability. So: what has happened to mortgage rates over the last couple of years? Anyone know? There’s a clue right there at the end of the Treasury source’s quote. “The British economy is turning a corner”. Is it? Interesting. From what?3

It is easier to warn that your opponents’ irresponsible economic plans will lead to big mortgage rate rises if you haven’t just presided over big mortgage rate rises which mortgage-holders are still paying.4 It is harder to persuade people that your opponents are a risk when you are the risk.

All of which may help to explain this recent quote from a “senior Tory” to the Telegraph:

“It can’t be that you go into an election where our main dividing line on tax and spend is the £28 billion, [No 10] need to come up with something better than that.”

And it may also help to explain two new schemes which the Conservatives are reported to be considering, as ways of sharpening up their economic attack on Labour.

Scheme number one was briefed to the i over Christmas as a “spending trap”:

Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt are plotting a spending trap for Labour by dictating the amount of money available for public services before the next election.

The move would force Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves to decide before the election how much they want to allocate to each department and where they would make cuts.

This raises a number of questions, including “Eh?”, “Does it really?” and “But why though?” It is trivially true that if Labour are in government after the next election, they will inherit a set of spending allocations from the Conservatives which will stay as they are unless and until they change them. It would be perfectly reasonable for Labour to say that they will hold a spending review at the earliest opportunity following the election, and equally reasonable for them to say that they won’t prejudge what those allocations will look like until they have seen the books. This move wouldn’t force them to do anything at all.

The “trap” gets weirder, though:

Another option under discussion would be for Mr Hunt to announce the total “envelope” for the spending review, determining the size of the funding pot available to all departments in total, but not decide on the exact allocation of funds.

For a start, Rachel Reeves will, if she is Chancellor, be in a position to change the size of the envelope: it will be open to her in principle to raise or lower taxes, and she has already announced a number of tax changes she plans to make (you can love them or hate them or think she should go further, but the point is she’s mentioned them, and so she’s already committed to a different overall spending envelope from the Tories).

But more importantly, at this point it is impossible to understand how anybody could describe what the Tories are doing as a “trap”. If they announce a total spending envelope but not the departmental allocations, then any challenge they make to Labour to set out Labour’s departmental allocations can quite reasonably be met with the response “Why should we, if you can’t be bothered to do it yourselves?” You can’t set a dividing line, or force your opponents to commit to something, by explictly refusing to take a position yourself.

Scheme number two was briefed to the Telegraph just before new year.

Downing Street officials are looking at toughening up how borrowing is treated in the Government’s fiscal rules in an attempt to “flush out” Sir Keir over the issue. Sources suggested this would put political and media pressure on the Labour leader to explain how he would fund his policies within the rules.

Government insiders believe the move would deliver a “sting in the tail” which will expose Labour’s spending plans such as its £28 billion commitment to tackle net zero.

Again: this isn’t hard for Labour to deal with, or at least no harder than anything Labour is facing already. Labour doesn’t have to follow Conservative fiscal rules. It particularly doesn’t have to follow Conservative fiscal rules that even the Conservatives didn’t think they had to follow for the previous 13 years either. Labour can simply say: we have our own tough fiscal rules, and all of our spending plans will be subject to them.

Labour certainly has vulnerabilities, and the Conservatives will certainly increase their attacks on their spending plans, and the risk they pose, over the course of 2024. Labour will need to keep reassuring the public that they can be trusted on the economy. But the fact that the Conservatives still haven’t worked out what their attack is on Labour’s biggest source of internal economic angst, and that they are coming up with increasingly hare-brained schemes to trap them with, should provide Labour with some reassurance of their own.

I wrote about the £28 billion pledge, why there is an internal Labour Party argument about it, and what I think about it, in my previous post on Dividing Lines.

The graphic attributes the quote to the Telegraph, but as this extract from the article makes clear, the Telegraph itself attributes the quote to a Treasury source - which is to say, a Conservative special adviser. So this is the Tories quoting themselves and trying to make it look as if they’re quoting someone else: the quote-attribution equivalent of money laundering.

Here’s today’s Mail front page, which fails to notice that anyone getting a new mortgage deal now will almost certainly be paying more than they were previously - just not by as much as they would have done if they had got a new mortgage deal a few months ago. They will be worse off than they were last month, and it is not obvious how this will make them keener on the Tories than they were last month.

To quote another headline on the same front page, these people are not going to regain the figure they had ten years ago, and that is not going to make them happier.

“put political and media pressure on the Labour leader”

They really do play politics on easy mode don’t they