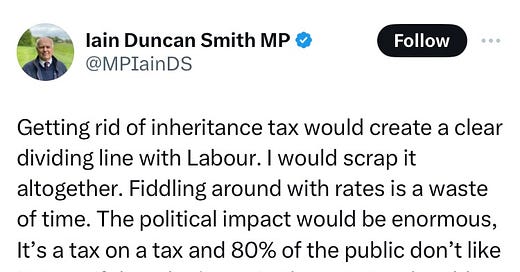

There are few more reliable ways to create a fuss on Twitter than to be a prominent Conservative and tweet something. Noted political strategist Sir Iain Duncan Smith achieved this the other day with the following political strategy advice:

This provoked the kind of reaction Sir Iain, as a noted political strategist, would have anticipated.1 Much of this reaction focused on his argument that scrapping inheritance tax “would create a clear dividing line with Labour”. He was quoted as part of a Telegraph article headlined “Senior Tories urge Sunak to be bold and scrap inheritance tax” in which Duncan Smith was quoted alongside former cabinet ministers David Jones and Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg making the case for abolition. Jones made a similar argument about the politics of the tax change:

Mr Jones, the former Welsh secretary and Brexit minister, said the Chancellor should review “every tax” and go for growth but the political advantage of scrapping inheritance tax was “extremely potent” as Labour could not and would not follow the Government’s lead.

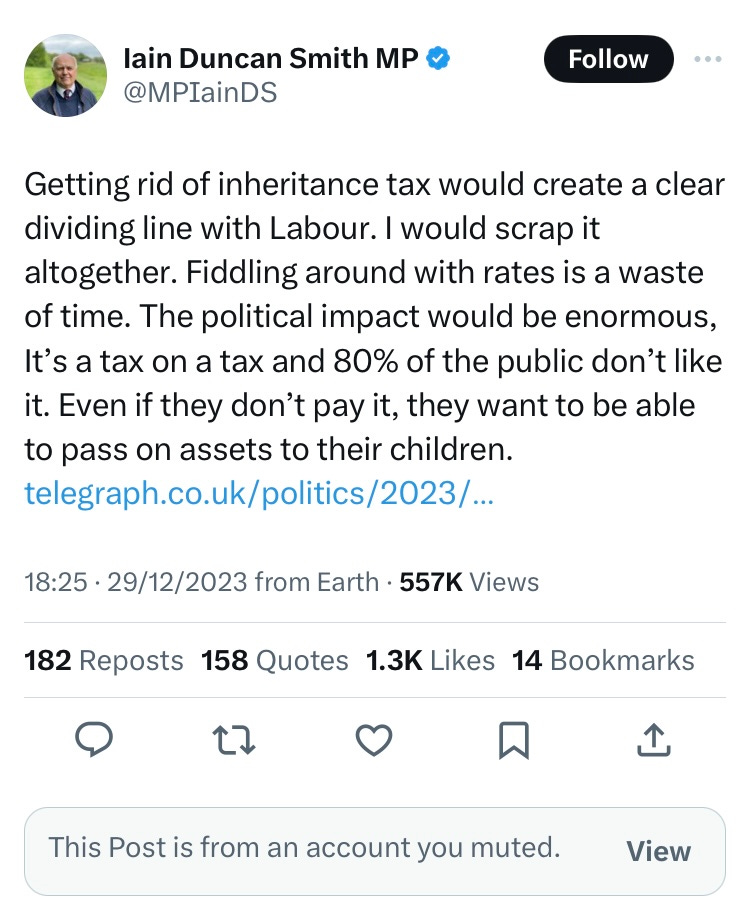

Talking about policy changes in terms of their political advantage, rather than their merits as policy, is a way of making it look as if you think politics is all a game. Hence this reaction to the Duncan Smith tweet from historian Robert Saunders:

This is an understandable position. But it glosses over two crucial facts: the sincerity of the demand, and the intended audience. If these former ministers were arguing that abolishing inheritance tax is a bad policy that would nevertheless be popular, it would be fair enough to attack their cynical game-playing, their willingness to wreck the economy in the service of maximising Tory electoral advantage. They are not. They sincerely believe that inheritance tax is unjust and that it should be abolished. And they are aiming their message at strategists in Downing Street who (the former ministers hope) are convinced of the merits of the policy, but who (the former ministers fear) are worried that doing what they think is the right thing in policy terms will lose the Tories votes.2

There is nothing new about senior politicians briefing about policy changes they would like to see their parties adopt. In general, these briefings are an irritation to their respective leaderships rather than being seen as helpful and constructive contributions. It is very common for them to be couched as strategic advice rather than policy advice: providing examples of the belief held by people right across the political spectrum - almost all of whom must be wrong - that the political party that they personally support would be doing better electorally if only it adopted more of the policies that they personally support.3

Dividing lines are not inherently bad things. They are inherently political things. A dividing line is a policy position that both a) differs from the equivalent policy position of a party’s main opponents and b) conveys something important about who or what a party is for and what it believes in. Often, both parties agree on where a dividing line is, disagreeing only on how to characterise it and on which side of the line is right. And often, the creation and elimination of dividing lines is part of a political war of manoeuvre, with parties seeking to open them up or close them down, mirroring what their opponents announce in order to prevent attacks or opposing them in order to allow them something new to aim at. In all of these cases, they are trying to define what the election, and the political choice it represents, is and is not about: to stop it being about the arguments they think they will lose and make it about the arguments they think they will win. And in both cases, it is difficult or even impossible to separate the politics from the policy.

The argument inside the Labour Party about the status of the £28 billion per year Green Prosperity Plan is a perfect example of an internal disagreement about whether it is better to have a dividing line or close it down. As with almost all such disagreements, both sides have a point and neither can be easily dismissed. And both sides’ points are about politics as well as about pure policy. Committing to invest £28 billion per year on green infrastructure (£20 billion over and above existing government plans) creates two dividing lines, not one. The dividing line Labour likes is that the additional investment is to be spent on things designed to hasten the UK’s transition to net zero, to crowd in private investment, to create jobs and to boost economic growth. The one it dislikes is that this all costs more money than the Tories have said they will spend, even though Labour has elsewhere worked very hard to close down the space in which they can be attacked for spending more than the Tories.

That on-the-one-hand-this-but-on-the-other-hand-that paragraph is not, by the way, an attempt on my part to get out of having an opinion; it is an attempt to recognise that the dispute is real and that it is not one with goodies and baddies: politics is hard. My view, for what it’s worth, is this: first, I think that if Labour thinks this investment is worth making, despite the real downsides, then it should continue to say it will make it; second, I think it is worth making, in my capacity as a professional not-an-economist and liker of nice things; third, I think there is a winnable political argument to be made, which Labour is yet to develop fully or lean into, about the investment-for-green-growth trade-off; fourth, I think the political downside of backing away from a commitment that matters to a big part of what we might call Labour’s green intellectual policy wonk support base, as well as its broader left flank, is significant; fifth, I think the Tories can attack dropping the policy in the face of adversity almost as effectively as they can attack keeping it; sixth, I am not an idiot and I am perfectly well aware that arguments two to five in this very long sentence are examples of me saying that I think that the political party that I personally support would benefit electorally from policies that I personally support.

Labour’s green investment argument, and the Tories’ inheritance tax argument, have yet to be resolved. The reason why Sir Iain Duncan Smith, David Jones and Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg4 are making the argument about inheritance tax in the pages of the Daily Telegraph, a paper which broadly agrees with them, is that they know they might not win it: the last time it came up the Government backed away precisely because they were worried about the politics, not the policy. We know this because they briefed at the time that they dropped it as a result of Labour criticism - the subject of a previous edition of Dividing Lines. Arguments about whether any given policy are both right in principle and popular in practice are at the heart of more or less any political decision in a democracy. Sir Iain Duncan Smith is wrong, but - as so often in his long career - he is sincerely wrong. We shouldn’t get cross with politicians who think that the policies they believe in will win votes. We should ask if they’re right.

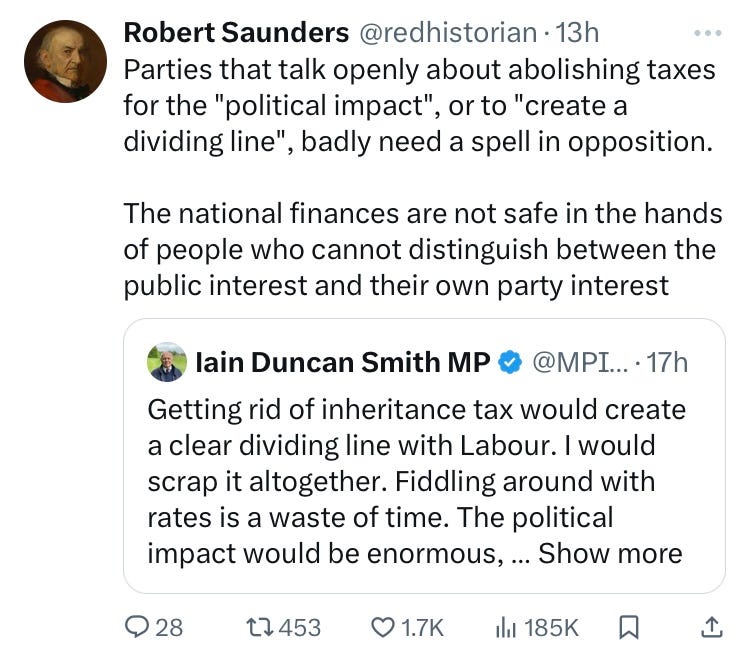

You’re probably wondering what that muted account in the screenshot was. So was I, which is one of the weaknesses of the mute function: it makes you look. Anyway, I looked:

I think we can all agree that muting was the right decision, and that there are few more tedious - if also few more successful - models of generating large-scale Twitter engagement than systematically posting “Waaaaargh” under anything tweeted by a Tory.

It’s also worth acknowledging that for most MPs, most of the time, there isn’t a strict distinction between the national interest and their party’s interest, because they sincerely believe that it is in the national interest for their party to be in power. This is a perfectly coherent position to hold: one of the main reasons they think it is in the national interest for their party to be in power is that they think their party is the most likely, all things being equal, to enact the kinds of policies which they think are in the national interest.

There are lots of policies that I personally support. But it would be an extraordinary coincidence if any of them were also election winners. This is annoying, but so is life.

You can take any random group of Conservative MPs at this point and two thirds of them will have been knighted.

Loved this. I think people just find it hard to believe people can be so sincerely wrong. "Surely someone this wrong must be insincere! Nobody could possibly disagree with me this much, they must also be evil and also probably lying!"

This is a very balanced argument, which I wish more people would make. Instead of demonising the opposing party, grapple with the substance of the policy proposal, even if you believe it's actually about electoral advantage. Being able to boil down why a policy proposal is wrong, for the TV interview/soundbite format, is hard but worth doing. In this instance, it's not hard at all. I'd like to see more pithy arguments against the policy from Labour, although at this stage anything the Conservatives propose is going to land badly. But I don't want to see Labour trying to do "politics on easy mode", as this certainly won't help once in government.