Not on your side

On telling your opponents their attacks are working

It’s always flattering when a journalist wants your opinion on something. For example, yesterday the BBC asked me to comment in my capacity as a former political adviser on the story that Keir Starmer had chosen Beethoven’s Ode to Joy as one of his favourite pieces of classical music, even though - as I acknowledged to them - I’ve never been directly involved in helping a politician make musical choices like this. As a result, and somewhat to my bemusement, readers of BBC News online were treated, over six whole paragraphs, to the following crucial insights from me: that Starmer probably chose Ode to Joy because “he just likes it”, and that Ed Miliband’s choice of Angels by Robbie Williams as one of his Desert Island Discs selections was something I’d have advised against, “but that is just because I don't like it”. I stand by these judgements, but I am not sure I added much to the story.

When I was a political adviser, briefing the media wasn’t usually part of my job, and it shows, doesn’t it? That’s partly because I spent most of my time in a policy team with a culture of total public anonymity, and with a performative disdain for the kind of people who felt the need to show off like this (it’s not just showing off, of course, it’s a crucial part of a broader political communication economy in which my close colleagues and I played a separate role as content creators and behind-the-scenes advisers who left it to others to do the actual briefing, but the cultural divide was definitely there in my day).1 But it’s also because briefing the media is a skill that people build up with experience, and that you specifically recruit for, and it can’t be done effectively by just anyone.

Political parties want to get their message across, as clearly as possible and in a way that makes them look good and appeals to the public. Journalists want to report and explain what’s really happening, including things that are going wrong and things that undermine parties’ messages, and to make it as fun and interesting and gossipy as possible for their audience. And plenty of players in Westminster, from politicians to advisers to officials to other more-or-less-well-informed hangers-on (that’s me, nowadays) want to feed that machine in ways that help their own agenda, which may well include the agenda of making sure they’re the kind of people journalists will want to talk to again (that may or may not be me, nowadays). And the interaction and conflict between all of these different motives makes up the news.2

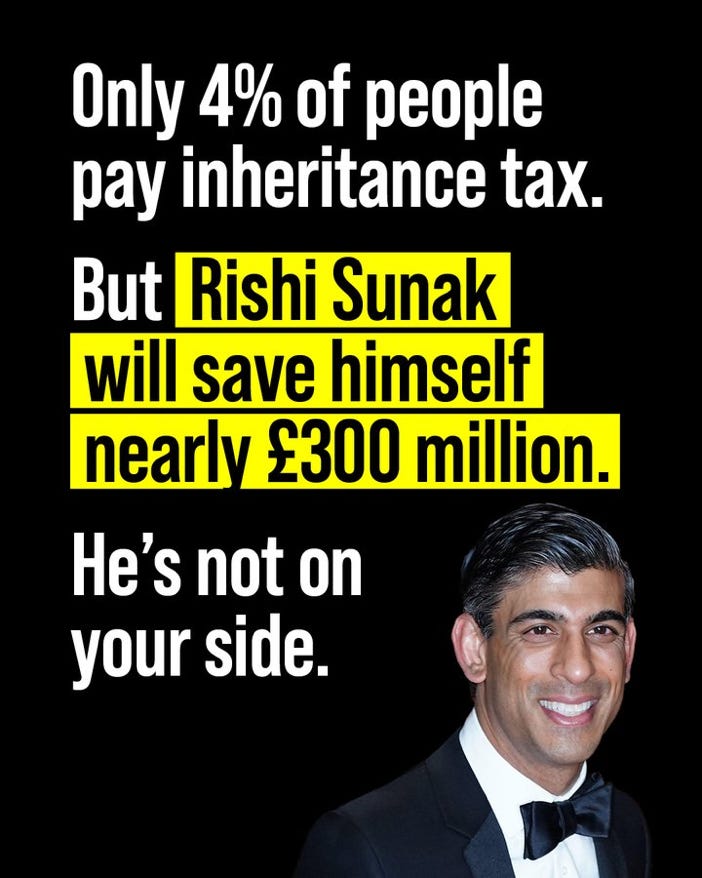

Over the last few weeks, one of the things political journalists have picked up from their sources on the Conservative side was that Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt were strongly considering cutting inheritance tax in the Autumn Statement. There was some public debate - of the kind we are all very familiar with by this point - about whether this would be a good idea or not, both in terms of the economic merits of the policy and of whether it would help the Conservatives or not. In the end, they didn’t do this.

Today, some briefing has emerged explaining why they didn’t. According to Bloomberg, the tax cut was seriously considered, and may yet reappear in the Spring Budget:

On the economy, Sunak hopes to be able to announce more tax cuts at the spring budget. If inflation falls below 3%, he intends to make good on his leadership election pledge to cut income tax, according to people familiar with the plans. He is also considering reviving proposals to cut inheritance tax, a policy which was worked up in full by Treasury officials before this week’s Autumn Statement but dropped following Labour criticism that it would be a sop to the wealthy, they said.

Bloomberg journalist Alex Wickham tweeted with an extra snippet:

inheritance tax cut policy was worked up in full by the Treasury in recent weeks but dropped after Labour attacks like this >>>

Wickham, we can presume, didn’t make this up. Someone has briefed him both that the inheritance tax cut idea was a serious proposition which was ready to be put into the Autumn Statement and which might come back later, and that it was dropped as a direct response of Labour criticism. As an actual Labour source put it to me (see, I can do political journalism too), “What an amazing thing to brief out: ‘We didn’t do a crucial part of our offer because of a hastily pulled together social media advert by our opponents. Hopefully they’ll stop doing them’.”

Nothing boosts the morale of a political party’s attack operation like being told that their work has directly led to an opponent’s policy being dropped. Nothing is more likely to persuade them that they are more or less getting it right, and that they should stick at it. And that is why it’s better - if you are briefing a journalist - not to say it, even if it’s true.

(The argument over inheritance tax is fairly straightforward whenever it comes up: it is a fact that not very many people pay the tax, but it is also a fact that the tax is unpopular, including with people who are unlikely to be directly affected by it. It is a fact that the main beneficiaries of cutting inheritance tax would be people who have or stand to inherit large estates, who are disproportionately likely to be Conservative supporters and who frankly include some actual prominent Conservatives, but it is also a fact that the principle that one should be able to pass on one’s wealth to one’s children is simple to make and broadly accepted. Both sides know all this, and even if both sides have arguments they agree with, they can never be fully confident that they have arguments that win. What this briefing has done is to make clear that the Conservatives are not convinced that the balance of these facts is in their favour when Labour pushes back using openly left-wing arguments, in the way that it did over the last couple of weeks - something it did not go without saying that Labour would do.)

The Tories might well come back to an inheritance tax cut in the Spring Budget. But this briefing makes it more likely that Labour will have the confidence to make the argument against it then. If that was enough to put them off last week, it’s not obvious that it won’t be enough to put them off closer to an election. This is a little briefing with big consequences. Sometimes, when a journalist calls you, it’s safer just to tell them you don’t really like Angels.

This culture came, I think, from the fact that the team I was in had a major focus on attack and rebuttal, spending much of our time combing through public statements trying to find things that would embarrass our opponents, and we were always very aware that our opponents were doing the same to us. One way to avoid being embarrassed by your public statements is not to make any, ever. My old blog, which I wrote from 2004-2007 and which included some pieces I was quite proud of at the time, was deleted the day I accepted a job with Labour and you won’t find it now, although I’ve no idea why you’d try and it’s hard to imagine the Conservative Research Department finding it very interesting even in 2008.

This is not a fully worked-up theory of the interaction between politicians and the media and the socio-political consequences those complex motives and relationships create. It is a linking paragraph.

I will openly admit that I have a possibly idiosyncratic hatred of nepotism and that possibly stops me from understanding why people won’t see it the way I do, but I really think that yes people might currently think passing on wealth to one’s children is a right and preventing it could be unpopular, but there’s a flip side that Labour can sell that nobody likes nepo babies and why should young men who’ve done nothing and already been given an amazing leg up in life with the best education and social and business contacts also be given millions of pounds to give them another leg up over talented middle and working class kids.

If you change the story from the right to pass on wealth to the snotty little rich kids who’ve already had every benefit getting millions to help them win in business and life over hard working kids who’ve got their through talent and hard work then you could get people to support massive taxes on inheritance over a certain (high) figure to fund schools or the NHS or whatever, or better yet point out that tax has to come from somewhere so better to take the handouts off nepo babies and reduce income tax for middle class workers instead