If the Conservatives win the election, they’re going to put up fuel duty, meaning that it will be more expensive to fill up your car. How do I know this? Well, there are three reasons, and taken together the case is basically unanswerable.

First, the Conservatives do not rule out raising fuel duty in their fully-costed manifesto, despite explicitly ruling out a number of other tax rises. They say on page 57, “We have prioritised freezes in Fuel Duty”, which is true, but that’s a point about their record, not about the future, which makes the lack of a forward-looking promise all the more stark: after all, if they were going to do it, saying so would help them win votes, so it’s striking that they haven’t.

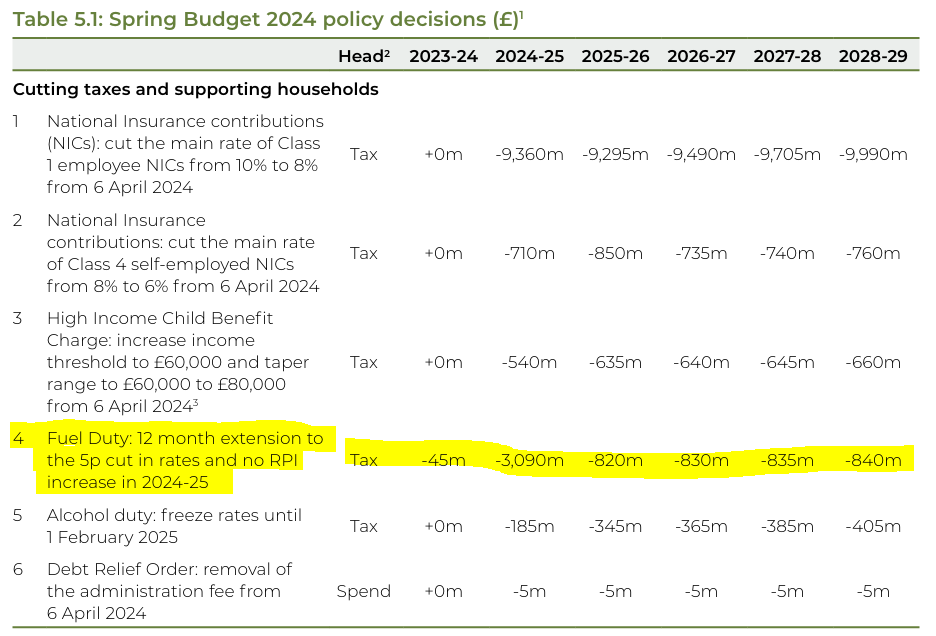

Second, a rise in fuel duty after 2024-25 is scored in the Red Book in the 2024 Spring Budget,1 which says on page 48 that “the government is continuing to support motorists and industry by maintaining rates of fuel duty at the current levels for a further 12 months, through extending the temporary 5p fuel duty cut and cancelling the planned inflation-linked increase for 2024-25”. The Conservatives’ future spending plans assume an increase in fuel duty, and we have to take them at their word.

And third, the Conservatives have a plan. They keep telling us they have a plan. If they have a plan, and their published plan involves a rise in fuel duty, and they are not promising not to raise fuel duty, I think we can take it as read that they are going to raise fuel duty. Otherwise their plan is not real. Let’s do them the credit of assuming they would not have a fake plan.

Now, weirdly, a lot of Conservatives would bridle against this argument, even though all it does is look at what they have said and taken them at their word. For example, when Keir Starmer refused to rule out raising fuel duty when questioned by Beth Rigby on Sky News (he didn’t rule it in either; he said “That has to be decided budget-by-budget, but my track record is we’ve supported the cap on fuel duty every single time it has come up”), Conservative Party Chairman Richard Holden was keen to point it out:

That’s weird, isn’t it? On this issue, Starmer is actually leaving more wriggle-room on fuel tax than the Tories are. Starmer won’t rule out raising it. The Tories are budgeting to raise it. Maybe Richard Holden doesn’t believe Jeremy Hunt’s numbers. Maybe Rachel Reeves, if she becomes Chancellor, will say that the state of the public finances means that she has no choice but to go ahead with the Tories’ planned fuel duty rise. Maybe she will find the money to cancel the tax increase the Tories are currently planning.

Anyway, the Conservative campaign is focusing hard on potential Labour tax rises, even when, as in this case, they are in their own Budget. Here are some of the tax rises the Tories say Labour are planning, represented in a variety of different graphics. There’s one with some people holding a red piggy bank:

There’s one with some Americans going for a walk:

And there’s one with a ballot box in a terrifying-looking mantrap:2

These all list the same five taxes, and it’s not entirely clear what all of them actually are. There are some clues in a Tory dossier on “LABOUR’S 18 TAX RISES” published last week, although they’re only clues because, confusingly, it doesn’t use the same headings for the taxes it discusses, and doesn’t seem to include all of them at all.

The “retirement tax” is the easiest one to dispose of: it’s not a new tax but the status quo. It’s simply Labour refusing to commit to going along with the so-called “Triple Lock Plus” under which the income tax threshold rises for pensioners as the state pension rises and the state pension is therefore never subject to income tax. As discussed on Dividing Lines the other week, this attack only works if you trust Labour’s promise to retain the Triple Lock: it amounts to “the state pension will go up under Labour, don’t worry”.

The “small business tax” and the “workplace pensions tax” and the “family home tax” are all, so far as I can tell, undefined: they are not specific taxes but general tax buckets with several taxes in them. The Tory dossier lists a number of taxes that are ruled out in their own manifesto but which Labour has yet to rule out, and over the last few days Labour has indeed ruled out some of these (for example, it is not going to levy capital gains tax on primary residences, because obviously it isn’t, come off it, that would be bananas).3 But Labour’s current form of words, that nothing in its manifesto requires tax rises that it has not announced and that certain specific taxes have been specifically ruled out, is as far as it wants to go. If there was ever a good illustration of the fact that governments need flexibility over taxes, it’s this government, whose flexibility over taxes is one of the main reasons why its attacks on Labour for potentially raising your taxes lack the potency they otherwise might have.

Finally, the “parents’ tax” does not appear in the Tory dossier: there is no specific claim in it that Labour is planning to raise taxes on parents. It is not entirely clear whether it is a reference to Tory plans to raise the threshold for parents to pay a levy on child benefit so that parents can earn up to £120,000 before paying it, or to Labour plans to put VAT on private schools (former Conservative Party Chairman Greg “I am CCHQ” Hands has referred to this as “Labour’s Proposed Parents Tax”), or both.

The Tories have tended not to centre Labour’s private school VAT increase in their attack, which is why I’m not quite sure if they’re intending to refer to it here, but some of their supporters in the media, notably the Daily Telegraph, have been less restrained. Here is a nowhere-near-exhaustive list of some of its recent headlines about Labour’s private school VAT policy. Starmer warned Labour’s private schools VAT plan could hit rural areas ‘like 1980s pit closures’ (honestly, this one is real), ‘I’ll have to quit being an NHS doctor and work in Lidl under Labour's private school tax raid’ (honestly, this one is real), ‘We moved to Spain to dodge Labour's private school tax raid’ (bloody economic migrants), Private school fees rise 6.2pc to brace for Starmer’s VAT raid (in previous years I guess they have just found different excuses for similar-sized fee rises which have happened despite not having a Labour government), Labour’s VAT raid will lead to ‘McDonaldsisation’ of education (I would simply avoid broadcasting my contempt for state education in quite such a brazen way, if it were up to me), ‘Tearful’ parents forced to remortgage under Labour's private school tax raid (remortgaging is an expensive business these days, for some reason which may also help to explain the Tories’ poor poll ratings), and How parents can dodge Labour’s private school fees raid and save £60,000. I already know the answer to the last one: don’t send your children to private school.

The Telegraph’s paywall may, by preventing more people from reading its stuff, be the last remaining barrier to a Labour landslide.

Despite the fact that the Telegraph’s coverage of Labour’s VAT plans has reached a kind of fugue state, the Tories themselves have tended to stay away from it. The reason this kind of thing is confined to Tory-leaning newspapers and is not placed front-and-centre of the Conservatives’ campaign is very simple: it is electoral kryptonite.4 That’s partly because of the pretty obvious fact that the overwhelming majority of parents do not send their children to private schools and the overwhelming majority of people in general did not attend them. The complaint foregrounds a set of concerns that most people simply do not have: the difference between private school fees as they are now and school fees with 20% VAT incorporated into them is the difference between a sum of money they do not dream of having and a sum of money they do not dream of having.

And acting as if it is a normal experience - that it constitutes a “parent tax” that most parents can relate to and fear paying - is a good way of alienating most voters. Anyone can concede that many parents who choose private education for their children are making sacrifices to do so, and that all of them have their children’s best interests at heart. But the implication (often, to be fair, not an intentional one) that follows on from that, which is that parents of children in the state system are not doing this, puts its advocates on the wrong side of a 90%-10% proposition. No sensible political party wants to be there.5

That’s why the attack on Keir Starmer at the Sky News Q&A last week, by someone who self-refutingly said “I’m an average working parent from London, and I send my daughter to a private school”, was such a gift to him, and why his initial response, “I absolutely recognise that many parents work hard and save hard to send their children to private schools because they have aspiration for their children. I equally accept that every parent, every parent has aspiration for their children whether they go to private school or not”, was such a big applause line.

The second reason the Tories cannot lean hard into this is even more important. You can’t protest about how terrible it is that affluent families may find it more difficult to take their children out of the state system without endorsing a claim that staying in the state system - something that more than 90% of parents do - is relatively bad for children. And if it’s bad for the children of better-off families, it’s bad for the children of worse-off families too, for whom the idea of buying their way out at any price is a fantasy. The Conservatives want to say that they have a good record on improving state schools, and they do have some evidence to point to. They simply cannot run the argument that state schools are good now alongside the argument that it’s terrible that children have to go there.

So one of the main taxes Labour explicitly says it wants to raise is one that the Conservatives have to be careful about talking about. The taxes the Conservatives want to say Labour will raise are not, by and large, real specific taxes. The Conservatives’ own tax plans are largely fictional and the only reason they can get away with it is that nobody thinks they can win anyway.

According to the Conservatives’ dossier, under their tax plans the overall tax burden will be 36.81% in 2028-29, whereas under Labour’s tax plans it will be 37.40% in the same year. That’s their attack. It doesn’t sound like much of a difference, does it? And they include, on page 11, a useful graph.

They want you to look at the hypothetical red line. But they can’t show it without printing the actual green line. That’s their record. That’s their problem. And that’s why their attacks on Labour’s tax plans have less potency than they’ve ever had before.

A quick “Look at me!” roundup: I have appeared in a surprising number of podcasts over the last week, which mostly goes to show that there are a surprising number of podcasts.

First of all, the most recent episode of The Election Tricycle focused on the fallout from the European Parliament elections, and we interviewed Zselyke Csaky of the Centre for European Reform.

I went on BBC Newscast following the Sky News leaders’ special, alongside Jo Tanner, talking about how we thought it had gone.

I’m on this week’s episode of Oh God, What Now? talking about the state of the campaign and… lots of other stuff.

And I’m on Times Radio’s The Election Shortcut podcast, which is basically a replay of their weekly politics panel, which I did with Jo Tanner (again) and Sean Kemp.

I also wrote for LabourList on the Labour manifesto and why, for once, the Labour manifesto might not be the end of a process but the beginning of something.

Ballot boxes take votes regardless of who they’re for, so this one will snap your hand off even if you try to vote Conservative in it. Incidentally, this is the latest in a short line of ads which are mocked up to look like real billboards in real streets, but which so far as I can tell only exist on the internet. There’s another one with Angela Rayner with a glove puppet:

I wrote about the Tories’ interesting use of Angela Rayner in their advertising a while back, so I won’t go on about this one, except to ask: why are Keir Starmer’s hands so old?

Some more CGT speculation was fuelled, hilariously, by Labour’s campaign director Morgan McSweeney liking a LinkedIn post advocating an increase in the tax. I am not convinced that this is how you announce a tax rise.

While I have views on state and private education and about the rights and wrongs of Labour’s VAT policy, with which you may agree or disagree, this whole argument is not about that. It is about how it plays and why the Tories are right not to lean into their opposition to it.

If Labour wins the election, and if it does enact this policy, I would be surprised if the Conservatives go into a subsequent election promising to reverse it.

The insincerity of a party who’ve bumped the tax rate to levels not seen since the rubble from the Second World War was fresh; achieved with the stunning inverse effect on knackered public services, attacking the opposition for the temerity of attempting to skirt a hole you’re still digging.

They are morally and intellectually bankrupt and the only thing that’ll save them as a coherent project will be a humiliating rather than catastrophic loss at the ballot boxes.