It’s not easy for parties that have just lost an election. For one thing, they’ve just lost an election, which is never pleasant.1 For another thing, in most cases they have to hold a leadership election, which is never pleasant for the party holding a leadership election, even if it’s quite fun for spectators. And for yet another thing, they have to watch the new government taking charge of things, getting on with taking the kinds of decisions they used to get to take, and setting the agenda they used to set. That’s not pleasant either.

The agenda the new Labour government has been setting in recent weeks, and the decisions they have been taking, have been focused not just on changing things and making things happen but on defining a narrative about the state of the nation and the economy, and about the mess they have inherited. They are helped by two structural advantages in particular: first, Labour now controls the government machine, the work of government departments, the information it dispenses, the messages it puts out. And second, the Conservatives have just been crushed in an election. We can overgeneralise about the reasons that happened, and we can observe that Labour’s share of the vote was low for a winning party, but there’s no getting away from the fact that the Conservatives’ share of the vote, at less than 24%, was low even for a losing party: most people are not currently predisposed to think they did a good job.

That means that the contest between the parties on whether the economy is in good shape or bad shape does not take place on a level playing field. Most people think it’s in bad shape. That’s a big part of why they kicked the Tories out. And that means that attempts by the Conservatives to argue that Labour has received a golden economic legacy are - to use a spatial metaphor that’s the opposite of a level playing field - an uphill struggle.

Sometimes, you do have to try to struggle your way uphill. And that’s what the Tories have been doing. Here’s a tweet about this week’s interest rate cut, which tries to make a broader point about how good the economy must be for there to have been an interest rate cut.

The graphic here, if not the caption, is very much the kind of graphic oppositions put out when they’ve forgotten they’re not still the government. And the overall message interestingly contradicts Rishi Sunak’s line during the election campaign, which caused a bit of a row at the time, that only a vote for the Conservatives could deliver low interest rates.

Well, voters didn’t back him, and interest rates have been cut anyway, so there.2

Here’s another Tory attempt to defend their economic record, this time by comparing the economy Labour inherited from them a few weeks ago with the economy they inherited from Labour in 2010.

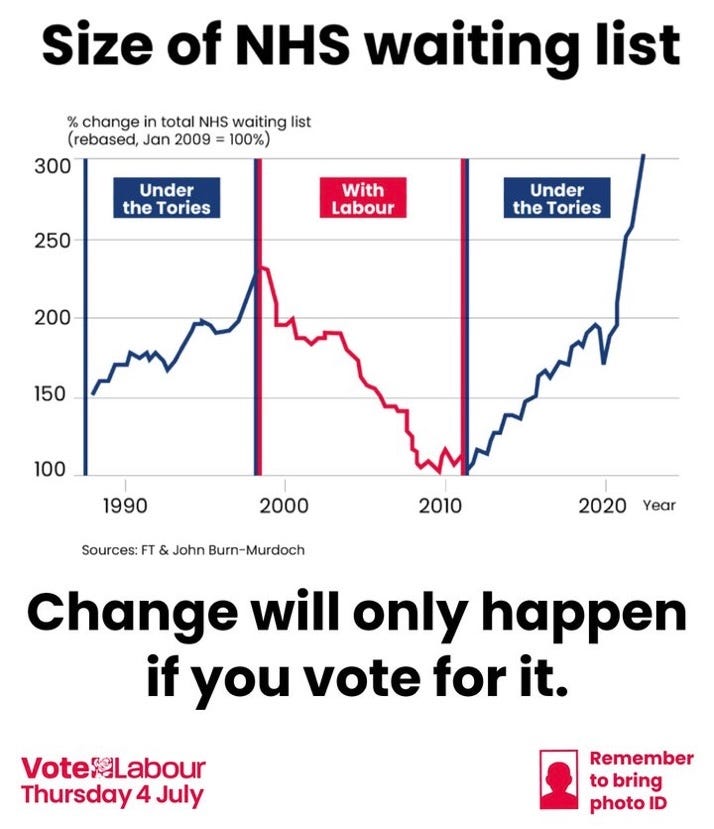

Now, obviously this kind of presentation is quite selective. Compare and contrast it with this graphic Labour repeatedly used before the election - this version of it is from election day itself - which is also about the difference between what the Tories inherited in 2010 and what Labour was set to inherit in 2024.

To put this in as non-partisan a way as possible, we can accept for the sake of argument both that both of these presentations of the figures are true so far as they go. As Stephen Bush helpfully put it in his (excellent) Inside Politics newsletter the other day:

The big picture politics here is that Labour has come into power at a time when people are deeply dissatisfied with the state of the public services and when the economy has had a prolonged period of sluggish growth going all the way back to the financial crisis in 2007.

When Labour came into office in 1997, it inherited an economy in great shape and a public realm in very poor repair. When the Conservatives came into office in 2010, they inherited public finances in a bad state, an economy still reeling from the financial crisis, but a state in good nick.

In 2024 people voted against the Conservatives in huge numbers, and for Labour in admittedly much less huge numbers but substantially huger numbers than they voted for the Conservatives, because they thought that the economy was crap and they thought public services were crap. That’s bad news for the Conservatives’ attempts to define their legacy, but it isn’t great news for Labour either, because now it’s their job to rebuild crap public services with a crap economy.

The difficulty of rebuilding crap public services with a crap economy is what’s behind the biggest party political row since the election. Rachel Reeves’ coldly livid identification of an in-year £22bn black hole, and Jeremy Hunt’s hotly livid denial of any such thing, are a key defining moment for both sides, and neither can afford to back down.

Hunt’s problem is that while it’s not wrong for him to point out that there is a considerable amount of transparency around the state of the public finances, meaning that Labour knew a lot about their inheritance before the election, nevertheless for every quote used by Hunt by the IFS’s Paul Johnson saying things like “The state of public finances were apparent pre-election to anyone who cared to look”, there’s another quote not used by Hunt by the IFS’s Paul Johnson saying things like “But at the top level, the fact that public services were in a mess, there wasn’t much money knocking around and this was going to be a struggle — that’s not a surprise”. The whole “everyone knew that public services were in a mess and there’s no money” thing isn’t a great way of pushing an “actually it’s fine and Rachel Reeves is making stuff up” narrative.

Reeves’ £22bn in-year black hole isn’t the same as the £20bn black hole over the course of the parliament that was identified by the IFS before the election, as this letter from the OBR, and yet another quote by the IFS’s Paul Johnson - “the extent of the in-year funding pressures does genuinely appear to be greater than could be discerned from the outside” - make clear. But nevertheless, the IFS did identify a £20bn black hole before the election, and although Labour did talk in general terms about the economy being in a bad state,3 all the incentives worked to prevent any specific number becoming a party political fight at that point: it didn’t suit the Conservatives to say that there was a £20bn gap, especially at the same time that they were proposing additional tax cuts, and it didn’t suit Labour to say that there was a £20bn gap at a time when, because the Conservatives weren’t saying it, the Conservatives were not pressing them to explain how they’d fill it. You can get cross about how these incentives worked if you like. Knock yourself out. But “Our tax cuts are crackers, fancy voting for us now?” and “Here are some extra tax rises from us that the Tories weren’t even warning you we’d do, what do you think?” are unattractive lines for parties to run with when they’re not being absolutely forced to, and so the debate didn’t happen.

Where the Conservatives want to go now is to an argument that Rachel Reeves is laying the groundwork for a wholly unnecessary set of tax rises that she specifically promised she wouldn’t make. It makes sense for them to go there, and so it’s worth unpacking why their claim doesn’t, strictly speaking, work.

First, when Hunt described Reeves’s statement as “a shameless attempt to lay the grounds for tax rises”, he was in effect acknowledging that those tax rises haven’t happened yet. And that’s important, because Reeves didn’t announce nothing. She cut some spending programmes, cancelled some capital projects and reduced the scope of the winter fuel allowance. And even if you think that Labour are just ideologically addicted to higher taxes for no particularly good reason, you are less likely to think that they are ideologically addicted to spending cuts. There are reasonable arguments to be had about whether Reeves’s cuts are either economically or politically wise. There are not really any reasonable arguments to be had about whether Labour likes doing this kind of thing, and that should give us a clue about whether they really think it’s necessary: they do. Departments are being told to find cuts, and told that they can’t have any new money, at the very start of a Labour government, and that should give us a clue about whether Labour thinks it’s in a hole. The Conservatives are of course within their rights to call for these cuts to be reversed, but they should bear in mind that they’re on the other side of the Treasury spending dossier now.

Second, the Tories’ claim that Labour are about to make tax rises they specifically said they would not make is - probably - flat wrong.4 The Conservatives have just spent a whole election campaign pointing out that Labour’s pledge not to raise income tax, national insurance or VAT left a whole lot of taxes potentially open to being increased. They can of course complain if other taxes Labour never talked about are increased, but it would be disingenuous in the extreme to move from “they haven’t ruled out these tax rises, look”, to “they said they wouldn’t raise these taxes, look”, about the exact same taxes.5

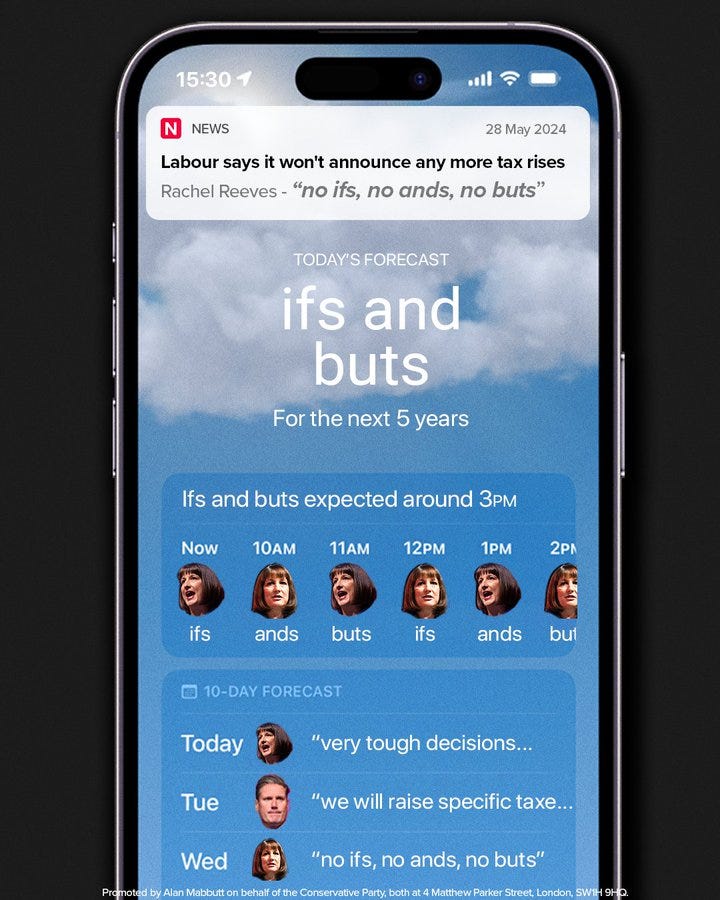

You can see what’s going on in the way the Conservatives are treating a line in a Reeves speech from May: “no ifs, no ands, no buts”. Here’s a slightly odd Tory graphic6 based on the quote.

And here’s what Reeves said:

I have been very clear that every policy we announce, and every line in our manifesto, will be fully costed and fully funded.

No ifs, no ands, no buts.

That is the attitude I will take into the Treasury.

This is, as is clear here, a limited point about the manifesto. Before the election Labour, like all opposition parties going into elections, set out a series of policies it wanted to put into effect over and above the existing government’s plans, and a series of revenue-raising mechanisms it wanted to use to pay for them. It did not announce policies it couldn’t pay for with the tax rises it said it would implement. That’s what the “No ifs, no ands, no buts” line refers to. It’s not a “we won’t raise any taxes we haven’t already set out” pledge. It’s a “we won’t raise any taxes we haven’t already set out to pay for any promises we have already set out” pledge. The move that’s coming, which Reeves has been setting up in the last week or so, is from “we will raise some taxes we’ve told you about to pay for some policies we’ve told you about” to “we will raise some taxes we haven’t told you about because it turns out the Tories have burned everything”.

Of course, all of this is vulnerable to the classic “if you’re explaining, you’re losing” problem.7 And Labour tax rises, assuming there are Labour tax rises, which I do indeed assume, because Rachel Reeves says there will be some, come with political risks, including the risk that people might think of them as the kind of broken promises the Tories want to claim that they are. After all, having lost the election the Tories are not going to break any promises for some time. They do not have to work out how the hell to implement the public spending cuts that would have been needed to cover the additional national insurance cuts they promised, which means they can attack Labour’s choices instead. Losing elections is unpleasant, as I said at the start, but it has its upsides, and one of them is that none of this is their problem any more. With great powerlessness comes great irresponsibility.

Fortunately for Labour, they aren’t the only ones explaining, because the Tories are too. They’re still stuck trying to explain that the economy is strong, actually, even though it doesn’t feel that way to you and you just voted them out on the basis that it wasn’t. It’s understandable why they want to do this. But it’s unlikely to work. After all, the Conservatives tried to argue after 1997 that they had “left a golden economic legacy of low inflation, steady and sustainable growth and falling unemployment”, and they had much more of a point than the current lot,8 and it still took three elections and a global financial crisis for them to get back in.

The Conservatives might win the next election. There are potential routes for that to happen. But none of them involves the public becoming convinced that the economy was in good shape in 2024.

I know whereof I speak.

The reason Sunak’s interest rate comments caused a row at the time is that Sunak, and Conservative ministers in general, had previously argued that interest rates were nothing to do with them when they were rising, and now wanted to take the credit for the possibility that they might fall in the future - an economic version of the old “when Andy Murray wins he’s British and when he loses he’s Scottish” complaint.

Here’s a tweet from the Tories using a pre-election quote from Rachel Reeves saying “We know things are in a pretty bad state” as a defence of Labour’s economic inheritance, somehow.

That’s to say: it’s flat wrong unless they increase income tax, national insurance or VAT.

Obviously, “it would be disingenuous in the extreme to say this” is not the same as “they won’t say this”.

I really don’t understand what they’re going for here. Why the phone?

To be fair to Labour, they’re not explaining, I am, and I have nothing to lose.

I feel duty bound to say, in response to the anticipated criticism of friends and former colleagues who were part of the Labour operation at the time and who will be irritated by the way I’ve phrased this, that “more of a point” is not the same as “a point”.

The phone graphic is surely to resemble a weather forecast app.

There's another thing I didn't really see Sunak et al pulled up on much. Trying to take credit for reducing inflation (one of the dubious targets) but not taking responsibility for increasing it and blaming external factors. Yet the main lever for attempting to control inflation is interest rates, which are of course totally out of the hands of the Govt . So what levers did they really have as Govt and why didn't they pull them way back before it rose? Either they have them and use them (effectively or not) or they don't .

“most people are not currently predisposed to think they did a good job” - mate, they did a completely shite job for well over a decade. 24% is generous