Gaslighting

The difference between being in government and being in opposition is incredibly simple. In government you spend the entire time wondering why no one can see all the good things you've achieved. In opposition you spend the whole time moaning that people should realise just how bad everything is.

This leads to the most depressing aspect of opposition: part of you actually starts wanting things to get worse.

You might think that this is an appalling thing for me - someone who spent some time as a Labour adviser in government and opposition, and who openly wants the current Labour opposition to win - to say. And so I should come clean now and admit that the first two paragraphs of this post are not my words at all, but the words of David Cameron, writing as an opposition backbench MP in 2002.1

Cameron’s Guardian column, which ran from 2001 to 2004, was actually pretty good, as columns by MPs go: it’s recognisably him, with the breezy and slightly glib confidence of a former Conservative adviser turned PR executive turned MP, speaking in the voice of the common room rather than the common man, with the self-awareness and self-deprecation of someone who knows what he can afford to concede, conveying a hint of insidery indiscretion without ever actually straying off message or giving anything away. While he was more obviously disciplined in his language later, as leader, he was also better than most leaders at sounding natural when speaking in interviews or at the dispatch box: you can tell he wrote these columns himself, and enjoyed writing them.

This passage sums up the whole tone of the column pretty well: letting out a dirty secret that politicians aren’t supposed to admit, but doing himself no damage at all in the process. It didn’t stop his rise to the top; it helps illustrate how and why he got there.

After all: he is right, isn’t he? Why is Labour set, as the polls currently stand, to win the next election? There are lots of reasons, but perhaps the biggest one is that everything is crap. If everything were less crap, there’s a good chance that more people would be happier, and that they would be more satisfied with the government, and that they wouldn’t think it was time for a change.

And there is some evidence, on some metrics, that things are getting a bit less crap. Inflation is down and looks likely to keep falling. NHS waiting lists are not as high as they were. Last week’s growth figures showed that the UK is out of recession, although in my case I hadn’t actually been aware that we were in recession in the first place so for me the “UK is in recession” and “UK is out of recession” headlines arrived simultaneously, cancelling each other out.

For the Conservatives to have a hope of winning, people need to start hoping things might be getting better. And if there’s any risk that that might happen, Labour has to crush that hope at birth.

That was the idea behind Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s speech last week, delivered in advance of quarterly growth figures which were widely - and, as it turned out, correctly - expected to show better news than previous quarters. It was a framing speech, designed to shape coverage of better economic news than we’ve had for a while, and to tee up Labour’s response to it on the day, and to provide context for the way the Conservatives wanted to present it. Here’s the key section, coming just after Reeves has talked about some of the people she met during the local election campaign:

When they hear government ministers telling them that they have never had it so good.

That they should look out for the ‘feelgood factor’.

All they hear is a government that is deluded and completely out of touch with realities on the ground.

The Conservatives are gaslighting the British public.

This is smart, and it’s a good line, and it’s also incredibly cheeky. Because who’s gaslighting who here? It’s not true to say that government ministers are telling people that they have never had it so good. That’s a caricature of the government’s position. But it’s very difficult to rebut, because ministers are talking up the economy, because they have to, and that does fail to chime with the experiences of normal people with mortgages and rents and bills to pay and weekly shops that cost noticeably more than they did a year ago.

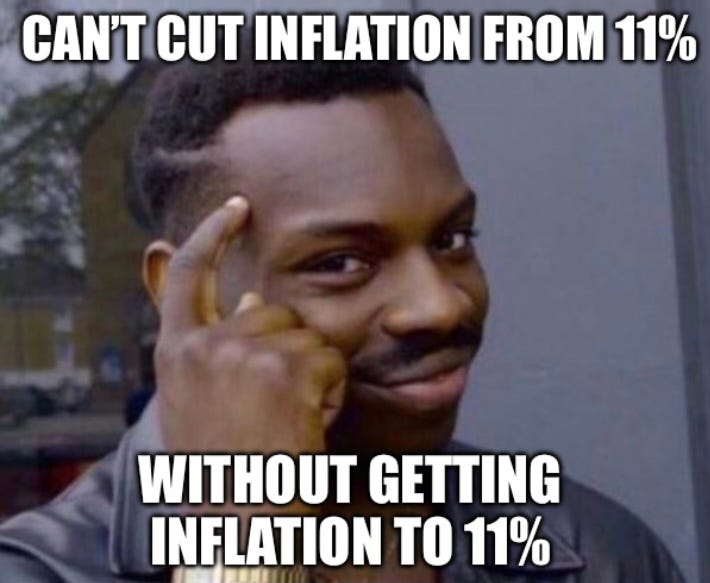

For example, look what happens when the Government talks about inflation coming down. Inflation is coming down, and that’s important and unambiguously good, but what that means isn’t that prices are coming down or that anyone is better off, but that prices are only going up a little bit from their already higher-than-ever levels. That’s pretty obvious, but it puts ministers in a bind because they can’t say that inflation coming down is good without looking as if they haven’t noticed this.

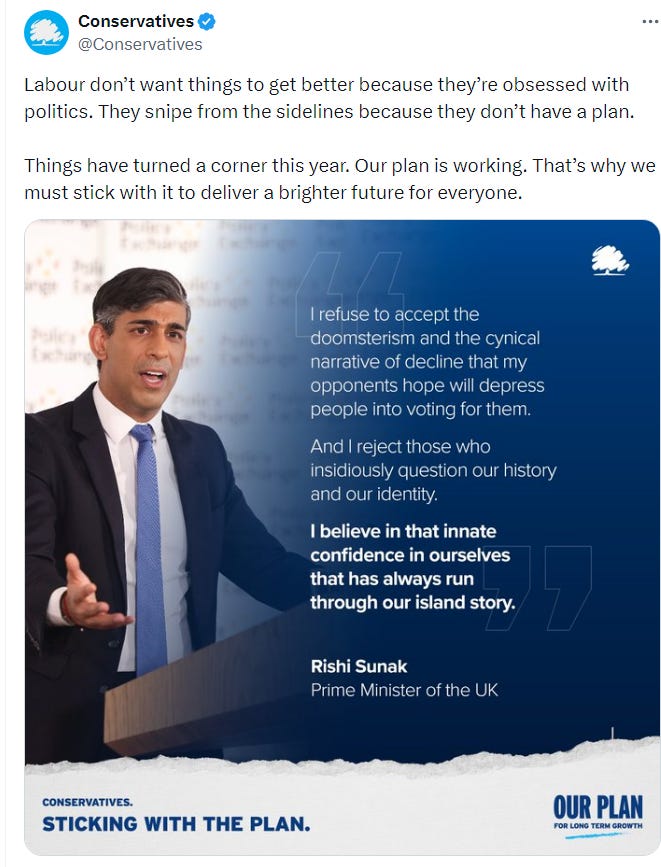

And the fact that the recent falls in inflation have been quite large is similarly problematic. Look at this Tory graphic, for example:

That’s nice, but what’s that little number at the top? 11%! Who was in charge when inflation was as high as that, because those guys sound terrible? What, that was you too? Oh.2

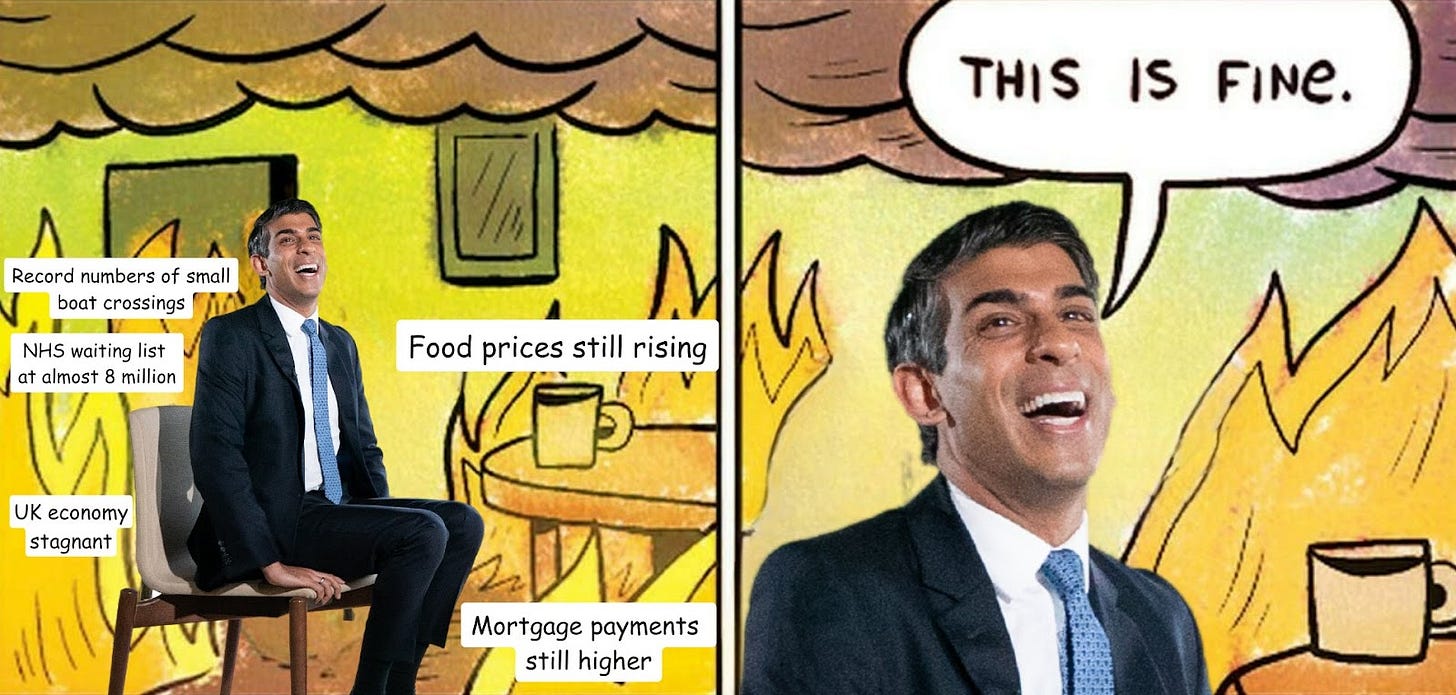

The political risk for the Tories of talking up their successes at a time when people are still dissatisfied with the state of the economy and of public services is that it allows Labour to portray them like this:

It’s clear that the Tories find this extremely annoying, which is the opposite of a reason for Labour not to do it. Rishi Sunak gave a speech this week aimed at framing his big election argument,3 and a lot of it was spent complaining that Labour isn’t nice enough and doesn’t give him enough credit. He even said plaintively, without quite mentioning Liz Truss by name, that Labour is trying to “reduce the last 14 years to 49 days”, a line which almost made me feel sorry for him and then didn’t.4

Sunak’s argument about Labour is that they want to talk Britain down (“maybe they can depress their way to victory with all their talk of doom loops and gas lighting and scaremongering about pensions”) because they have nothing positive to offer (“despite having fourteen years with nothing to do but think about the future, Labour have almost nothing to say about it. No plans for our border, no plan for our energy security and no plans for our economy either”). Here’s the key line:

Labour have no ideas. What they did have they’ve u-turned on. They have just one thing. A calculation, that they can make you feel so bad about your country, that you won’t have the energy to ask what they might do with the incredible power that they seek to wield.

And here’s the same argument in a tweet:

The problem with this is that this is gaslighting too. There are plenty of things you can criticise Labour for, but they have to involve engaging with the substance of their policies, not just pretending that they haven’t got any. You can disagree with every single policy in Labour’s five missions and their 116-page National Policy Forum final document, but what you can’t do is say with a straight face that Keir Starmer, a man whose conference speech was about the need for “a decade of national renewal” and who is laying out what is explicitly a two-term project, has nothing to say about the future. In the battle between “Labour has nothing to say” and “Labour has too many policies” I am a proud card-carrying member of Team Too Many Policies. That makes me a critic of the Labour Party too, I guess, but I’m one who has at least done the reading.5

Sunak can be accused of many things, but not of wanting the country to fail. Indeed, his speech was, in places, strikingly optimistic. Take this passage about the potential of AI:

Technologies like AI will do for the 21st century what the steam engine and electricity did for the 19th. They’ll accelerate human progress by complementing what we do, by speeding up the discovery of new ideas, and by assisting almost every aspect of human life. Think of the investment they will bring, the jobs they’ll create, and the increase in all our living standards they’ll deliver. Credible estimates suggest AI alone could double our productivity in the next decade. And in doing so, help us create a world of less suffering, more freedom, choice, and opportunity.

If this is right (I do not claim to know if it is) then with the opinion polls as they are that’s very good news for Rachel Reeves and very bad news for the Tories. Just as the current government can’t claim to be responsible for the rise of AI, the next government can’t claim to be responsible for whatever benefits it brings. But if they do preside over an acceleration of human progress, speedier discovery of new ideas, the improvement of almost every aspect of human life, new investment, new jobs, increased living standards, doubled productivity, less suffering, more freedom, more choice and more opportunity,6 that will probably boost their prospects of winning a second term. And the Conservative Party is unlikely to want to go on about how brilliant everything is.

David Cameron said in 2002, in an article I tried to gaslight you into thinking I’d just written, that wanting things to go wrong is “opposition disease - and it is highly contagious”. The Tories are at serious risk of catching it.

Welcome to new subscribers brought here via Helen Lewis’s curation of Substack Reads over the weekend - and thanks to Helen for recommending Dividing Lines. That little surge of new readers means that it’s probably time for me to do another book plug for Punch & Judy Politics: An Insiders’ Guide to Prime Minister’s Questions, which I co-wrote with my friend and former Labour PMQs prep team colleague Ayesha Hazarika. Ayesha - now Baroness Hazarika of Coatbridge - joined the House of Lords last week, and I can’t help noticing that I didn’t, so thank you for subscribing to this as a consolation prize, if you have. I also co-present The Election Tricycle, a weekly international podcast looking at connections and differences between this year’s general elections in the UK, USA and India; do please listen and subscribe to that too.

I didn’t put them in quotation marks because that would have given the game away. Incidentally, my last post, about the Tories still going on about Gordon Brown selling the gold 25 years ago, mentioned how weird it is to discover that events that feel recent to me actually happened a long time ago. Well, when you open that David Cameron article the first thing you see is a yellow warning sign saying “This article is more than 22 years old”.

That link is to an unredacted version of the speech helpfully tweeted by John Rentoul; the officially-published version has nine separate redactions of political content (political content isn’t supposed to be published on official government channels), making the officially-published version almost useless in this case.

On the one hand, maybe I should have overcome my inhibitions and just felt sorry for him. On the other hand, prime ministerial speeches shouldn’t evoke pity, and if as prime minister you do successfully achieve that then in a much bigger sense you’ve failed.

I don’t think it’s at all an exaggeration to say that we know more about Labour’s plans for the next five years than about the Tories’ plans for the next five years.

!

In Sunak's speech you quote him as saying

"Credible estimates suggest AI alone could double our productivity in the next decade"

I think he might be referring to this article in Fortune magazine, which has the misleading title "A top economist who studies AI says it will double productivity in the next decade"

https://fortune.com/2023/09/26/ai-economist-erik-brynjolfsson-productivity-boom-labor/

What the economist actually says is that the annual rate of *increase* in productivity will double from 1.5% to 3%.

One of Sunak's problems is that he thinks he's technically smart, but he isn't. Just the sort of person to be taken in by AI hype, sadly.

The sense of entitlement just oozes out of Rishi, he really does think he deserves a medal for doing the job of PM

This is so obvious and so off-putting it must be getting noticed by voters surely