Attacking yourself

Why Labour's Rochdale mess was not a candidate vetting problem

This was supposed to be a bad week for Labour,1 and in many ways it was, even if in the most important way - its ability to win competitive real-world elections by overturning very large Conservative majorities - it turned out not to be, much to the inconvenience of Big Narrative.

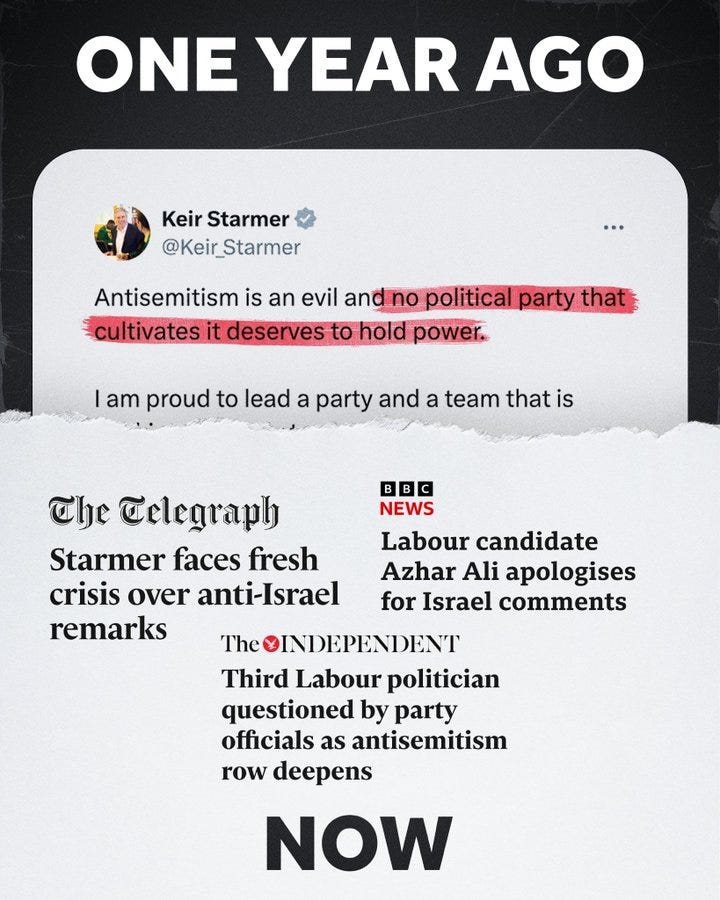

The reason it was still partly a bad week for Labour was that it was left with no real option but to withdraw its support from its by-election candidate in Rochdale, Azhar Ali, after a recording emerged of him making antisemitic comments at a private meeting. Shortly afterwards, Labour suspended another parliamentary candidate and former MP, Graham Jones, for comments he made at the same meeting.

One suspension was more controversial than the other. The idea that - as Ali claimed - Israel deliberately allowed a massacre of its citizens in order to give them a pretext for military action in Gaza, and that we can blame Jews in the media for decisions Labour takes, are pretty straightforward antisemitic conspiracy theories of a kind that nobody, let alone a Labour candidate, ought to be repeating. But it is less obviously problematic to ascribe - as Jones did - exasperation with Israel to world leaders, or to believe that British people should not fight for the IDF (although Jones was wrong as a matter of fact that it is against the law).

I can buy that Jones’ words were not as serious as Ali’s, but the critical fact here is that he attended and participated in a meeting where antisemitic conspiracies were voiced by a senior Labour figure and apparently didn’t challenge them or raise concerns later. Jones either didn’t notice a problem with what Ali said or did notice a problem but decided not to mention it, both at the time and later, when Ali was running to be candidate for Rochdale.

Some people have used this incident to complain about Labour’s process for vetting candidates, and to claim, or at least imply, that these two should never have been allowed to stand in the first place. This is, I think, wrong: it misunderstands what vetting involves, or at least what vetting with the resources of the Labour Party involves, and what vetting can and can’t tell you. And the behaviour of Graham Jones, more than the behaviour of Azhar Ali, helps to explain why. When assessing candidates’ suitability, you can only take into account what you know. Labour didn’t know what Ali had said, because nobody told them. And the person most obviously in a position to tell them, other than Ali, was Jones.

When I was in Labour’s research (code for attack) team we were only very rarely asked to get involved in candidate vetting, usually to provide chapter and verse on relatively well-known people who were already known to have problematic things on their public record and who were known to be thinking of standing for things, in order to ensure this was properly taken into account. That ad hoc process now appears to be a bit more systematic and better-resourced: witness this Labour job ad from last year for two Vetting Officers, which is not a position that existed in my day. The team I was in generally spent far more time researching, and had far more knowledge of, the potentially problematic pasts of Conservative candidates than of Labour ones.

In both cases, there are limits to the level of scrutiny that can be gone into, given the information that tends to exist at all. The techniques are the same, whether your focus is on attacking your opponents or minimising the space for your opponents to attack you. Realistically, you can look for media reports about prospective candidates, you can trawl their social media if they have any, you can see if they’ve written any articles or blogs or if they’re the kind of person who comments using their own name underneath online news articles (if they use a pseudonym, you’re not going to find them), you can check Companies House,2 you can in some cases talk to people you know who know them; but most people don’t have that much on them that you can find out from a desk.3 And most people who get as far as applying to be a parliamentary candidate have thought about this kind of thing already, which mostly means not so much covering your tracks as living the kind of life that doesn’t leave tracks in the first place.

There was a moral panic a few years ago about social media normalising a level of public sharing of private lives and problematic opinions and embarrassing photos that would make it difficult for anyone born after about 1990 to have a political career. As it turns out, people born before that still tend, if they have stayed out of the news, to have little that’s discoverable about them unless you have the time and resources to interview people who know them and who you don’t already know (which Labour absolutely does not). And most people born after about 1990 also don’t have that much that’s problematic on their social media, and even if they do most of it can be written off as the kind of thing young people say and do.4

In the Ali case, complaining about the quality of the vetting seems to me to miss the point completely. He already had a history of representing the Labour Party at senior levels - something that provided a prima facie case (to be clear, only a prima facie case) that he passed the bar for representing the Labour Party at senior levels. He did not, so far as I know, have problematic statements, antisemitic or otherwise, on public record. He had said problematic things in private. It is not at all obvious to me how any vetting process could have found these out unless a) he mentioned them; b) someone else did. As it turns out, someone else did have evidence of the problematic things he had said, and chose to pass it on to someone other than the Labour Party (reportedly it was passed to “Tory supporters”, and later made its way to the Mail on Sunday).

People, including people who attend private meetings with Labour representatives, have a right to wish Labour ill, and to use the information they have in ways that cause Labour maximum difficulty - in this case, holding on to damning information that would force Labour to drop its support for a candidate until it was too late to replace him, or passing it to Labour’s opponents. There’s no point complaining about this: nobody who doesn’t want to help the Labour Party is under any obligation to do so.

Similarly, there is no point complaining about the Conservatives wanting to make hay with all this. Of course they did, complaining (legitimately) about the content of Ali’s comments, and (more tenuously) about the delay in dropping him as a Labour candidate. The line they want to take is that it shows Labour hasn’t changed.

Ali should have been dropped sooner, but the problem with the claim that this shows that Keir Starmer isn’t committed to tackling antisemitism within the Labour Party is that he was dropped, and pretty quickly. But as I say, you can’t get cross with the Tories for saying it.5

What you can get cross with them for is absurd levels of overreach, like this one, in which they edited a video of Sadiq Khan saying “A party like mine that is proud to be anti-racist, but also antisemitic” to remove the immediate self-correction where he said “I beg your pardon, tackling antisemitism”, with the caption “Sadiq Khan says the quiet part out loud”:

Conservative Chairman Richard Holden tried to defend this, claiming “It’s not been edited, it was clipped”. The problem with this fatuous defence is that it gives the game away. If you want to say that Labour isn’t serious, you have to use arguments that can be repeated with a straight face. Even when Labour has a bad week, it doesn’t automatically follow that the Conservatives will have a good one.

On this week’s Election Tricycle we discussed the role of age in politics in our three countries: why age plays differently for Biden and Trump, how Modi is dealing with being as old as the elder statesmen he once replaced, and why the UK’s leaders are at least a generation younger. You can listen on Apple, or on Spotify, or via this Podfollow link. And we also have a longer edition for Premium Subscribers, with exclusive additional material. For complicated reasons to do with the fact that I have a free Substack and my co-hosts don’t, for the time being this is only available to paid subscribers of my co-host Emily Tamkin’s Substack ET Write Home.

It was, however, a good week for me, in that it was half term and I went away to North Yorkshire with my family. This explains the relatively long gap between posts and, for those who notice these things, the sparse tweeting.

The Conservatives sometimes point out that only a relatively small number of Labour MPs have ever run their own business, at least compared to their own parliamentary party. You can make up your own mind whether this is a good, bad or irrelevant thing. But what it amounts to in candidate vetting terms is: you can only find a relatively small number of prospective Labour candidates on Companies House.

My absolute favourite ever problematic PPC story was in the 2010 general election campaign, when the Labour candidate for the safe Conservative seat of North-West Norfolk, Manish Sood, said, “I believe Gordon Brown has been the worst prime minister we have had in this country. It is a disgrace and he owes an apology to the people and the Queen”. This was a problem, and it was also very funny - to be clear, this was the Labour candidate - but it was absolutely not a vetting problem: he had never said it before, at least not in public.

I was at university with someone who was known even then to have political ambitions in the Conservative Party, and who got into trouble as a student in ways which some of us thought at the time would be fatal to his political career. In retrospect, this was impossibly naive of us: he was a student, and nobody in the real world would ever have cared. His political career is over now anyway, because he got into trouble in the real world in ways that were, to those of us who knew him then, wholly in character. But even when he got into career-ending trouble as a proper grownup, nobody was interested in the student stuff.

OK, you can. But you can get cross with the Tories for anything. Honestly, a bit of light and shade would help.

Now Labour have withdrawn their support for Ali isn’t there an opportunity for them to go further (particularly with Galloway lurking) to go all out in supporting the Lib Dem candidate? Send shadow front benchers up there, go the whole hog on tactical voting support and then be able to refer to that when we need the Lib Dems to accept they can’t win some seats come the general

To be clear this is just a thought bubble, I’m very willing to listen to reasons this is a terrible idea but I would think a Lib Dem MP for Rochdale is the least bad option currently on the table

I very much like how you have sufficient balance (having done all this yourself) to be able to take the cut-and-thrust of political attacks wirh relative equanimity. Yes, all parties do this to each other. Few people stop to consider that it's their actual job to do so. This is the real "grown ups in the room" attitude, which I fear we may be losing.