Jeremy Hunt makes for an unconvincing attack dog. That, in many ways, is a virtue. One of his strengths as a politician is that he comes across as quite unpolitical - as a nice man who is just trying to do the right thing, without any of the cynical opportunism that characterises more calculating operators. When George Osborne said anything at all, you could hear the political wheels turning. Jeremy Hunt doesn’t seem to have any wheels at all.

Some of Hunt’s guilelessness is real. His Budget speech jokes this week were mostly awful, in an endearing they-told-me-I-should-put-a-joke-in-here-so-here-you-go kind of way. His decision to get into a Twitter argument with an anonymous poster called Globe Emoji Žižek Capital looked ill-advised at best. And as I noted last year, his tribute to the late Alistair Darling, while sincere and generous, contradicted a decade and a half of Tory economic narrative.

But being unpolitical can be a very effective political tool. As Health Secretary before the 2015 election, Hunt’s approach consistently wrong-footed his Labour opposite number, Andy Burnham: expressing bemused disappointment that Labour was seeking to politicise acknowledged imperfections in the NHS when everyone should just be trying to make it better. People don’t like politics. If you can rise above it, you look better than the grubby people wrestling in the mud down there.

All Budgets are criticised, but Hunt’s Budget this week has been attacked for not being political or theatrical enough, for lacking rabbits pulled out of hats. Hunt managed to dampen speculation about a May election by producing a set of measures that just don’t look like the sorts of things you’d announce if you were about to call an election. Nevertheless, parts of it were deeply political, even cynical.

The most obvious of these was Hunt’s decision to scrap the non-dom rule to help to pay for his cut in National Insurance. It’s pretty obvious that although this helped to create headroom for a tax cut he genuinely wanted to make, the biggest motivation for doing something he had previously described as “the wrong thing to do” was to deny Labour a significant funding mechanism for several of its spending pledges. In a world in which Labour is committed to setting out how all of its policies will be funded, removing a revenue-raiser is a problem for them. The Conservatives set out the challenge to Labour - drop these policies or find another way of paying for them - in a briefing note sent to journalists shortly after the Budget:

The Tories say these are the policies Labour was planning to fund with £1.6bn from the abolition of non-dom status.

More NHS appointments (£1.1bn per year)

Breakfast clubs in schools (£186m per year)

More NHS equipment (£171m per year)

More NHS dental appointments (£111m per year)

Labour can boast about winning the argument on non-doms and mock a significant u-turn, but the painful fact remains: the Tories have eaten their breakfast clubs.

The benefit of Rachel Reeves’ commitment to fiscal rules is that she is able to argue that she will not play fast and loose with the public finances, contrasting herself and Labour with both Liz Truss and Jeremy Corbyn,1 and blunting some Tory attacks on Labour profligacy. The downside is that it makes it difficult for her to promise nice things, or even necessary things.

The political hole Hunt has dug for Rachel Reeves, however, has been unexpectedly matched by a political hole he has dug for himself. Because Hunt did not just say that he was cutting National Insurance by an additional 2p, but that his ambition was to eliminate it altogether, and “end this unfairness” of “the double taxation of work”. In an email in his name sent out by the Conservatives last night, he made that even clearer than in his speech:

At the last budget, we cut National Insurance from 12% to 10% — helping the average worker on £35,000 keep £450 more a year.

This time, we’ve cut National Insurance AGAIN — from 10% to 8%.

In total, across both tax cuts, that means the average British worker keeps £900 more a year.

But there’s further to go. I’d like to end the unfairness where people in work are paying tax twice on their earnings.

We want a simpler, fairer tax system where you only pay tax once.

If we stick with our plan that’s working, we’ll be able to make progress towards that goal in the next Parliament.

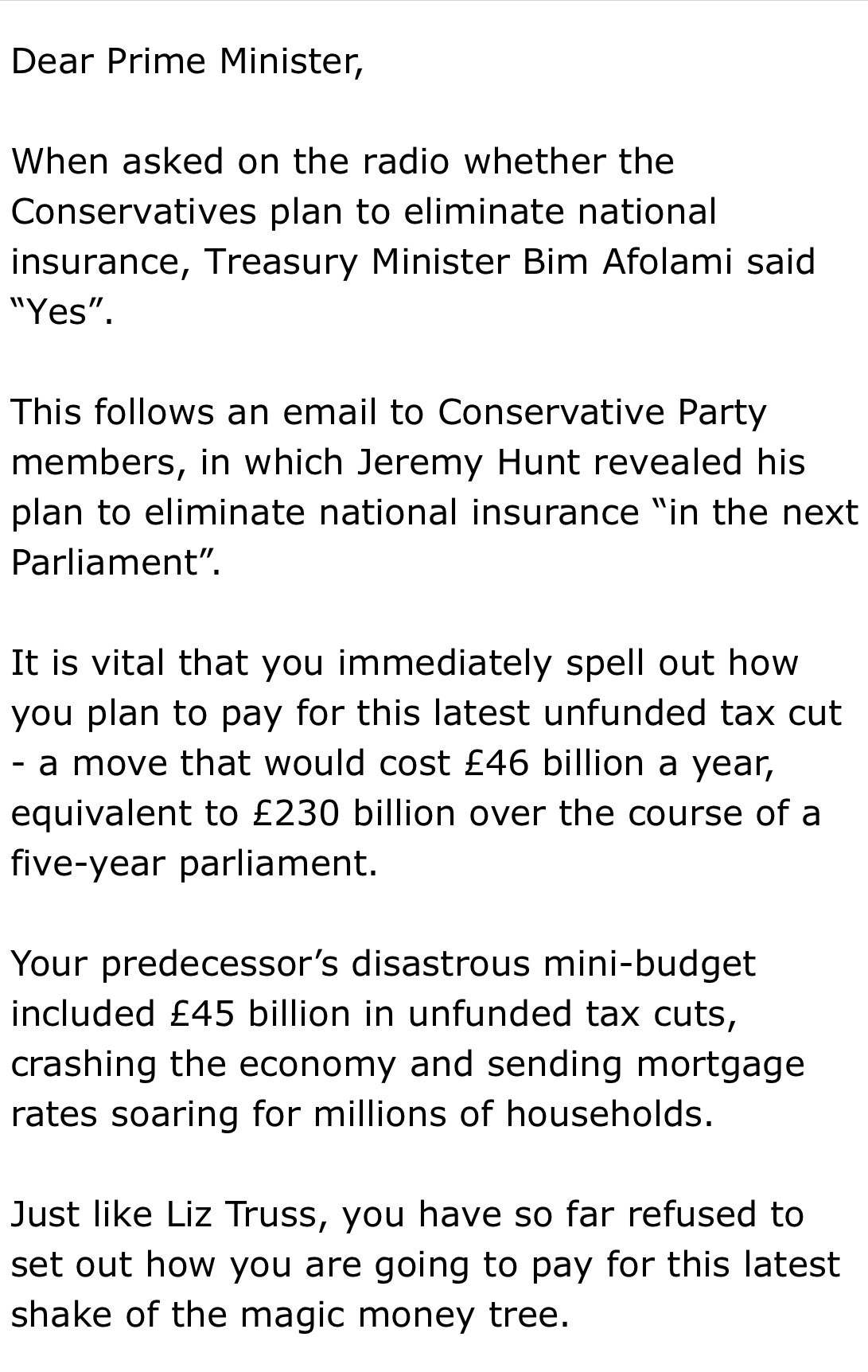

As someone in the shadow Treasury team undoubtedly said when they heard this: hang on a minute. You can’t complain about unfunded spending promises and then go around saying that you’d like to eliminate National Insurance altogether at some point. It may or may not be a good idea, but it is one with enormous implications for the public finances and the shape of the tax system: either you replace it with tax rises elsewhere or you forgo £46 billion a year of tax revenue. Labour would never get away with voicing an aspiration this big and this vague, and nor should they.

Hunt was astonishingly vague about this on Sky News:

“We’re not saying that this is going to happen anytime soon, and indeed that’s not the only way that you can end that unfairness of taxing work: you can merge income tax and national insurance.”

Come off it. The Chancellor can’t just wonder aloud idly about the various ways in which the tax system might be fundamentally restructured. He’s the Chancellor. He can’t go from “Wait for the Budget, it would be wrong to speculate in advance of an official announcement” to “I might abolish National Insurance at some point, maybe that would require a massive income tax rise, maybe not, who knows?”

These are questions the Conservatives are clearly uncomfortable answering - see Rishi Sunak’s appeal to a general sense that “I think what people can see from me, I think they trust me on these things, is that I will always do this responsibly” rather than setting out any kind of plan. For a party whose main chosen dividing line is “We have a plan, they don’t”, this is a problem.

No wonder Labour is having fun. Here’s Pat McFadden having fun:2

And here’s Darren Jones having fun:

At a time when the Tories would have wanted the story to be about how Labour is going to find about £2 billion to pay for things previously funded by the abolition of the non-dom rule, they are having to answer questions about how they are going to pay for the abolition of National Insurance. In a difficult week, the Tories have given Labour a line. Sometimes, Chancellors need to be a bit more political.

This Budget doesn’t look like a pre-election Budget, but another reason for being sceptical about a May election is this post on Full Disclosure about the Tories’ digital ad spending and how it doesn’t look anything like the kind of digital ad spending that you’d see from a party planning an imminent general election. I also enjoyed this post from Jonn Elledge on some of the reasons nobody has quite internalised the idea that the Tories might lose badly.

In this week’s Election Tricycle (our podcast about elections in India, the USA and the UK), Rohan Venkat, Emily Tamkin and I talked about money in politics in our respective countries, and in my case in particular about how much less money there is in UK politics. You can listen, and subscribe, here.

This is mostly unfair to Jeremy Corbyn, whose two manifestoes were published alongside detailed documents setting out exactly how the spending measures were going to be paid for, respecting the same fiscal rule Reeves is now following. I say “mostly unfair” because during the 2019 election campaign John McDonnell announced an additional £58 billion commitment to compensate women who lost out as a result of changes in the state pension age - a promise not accounted for in Labour’s costings document. This is, whether you approve or disapprove of the policy, quite a big omission.

I know. “The Tory’s”. Poor show.