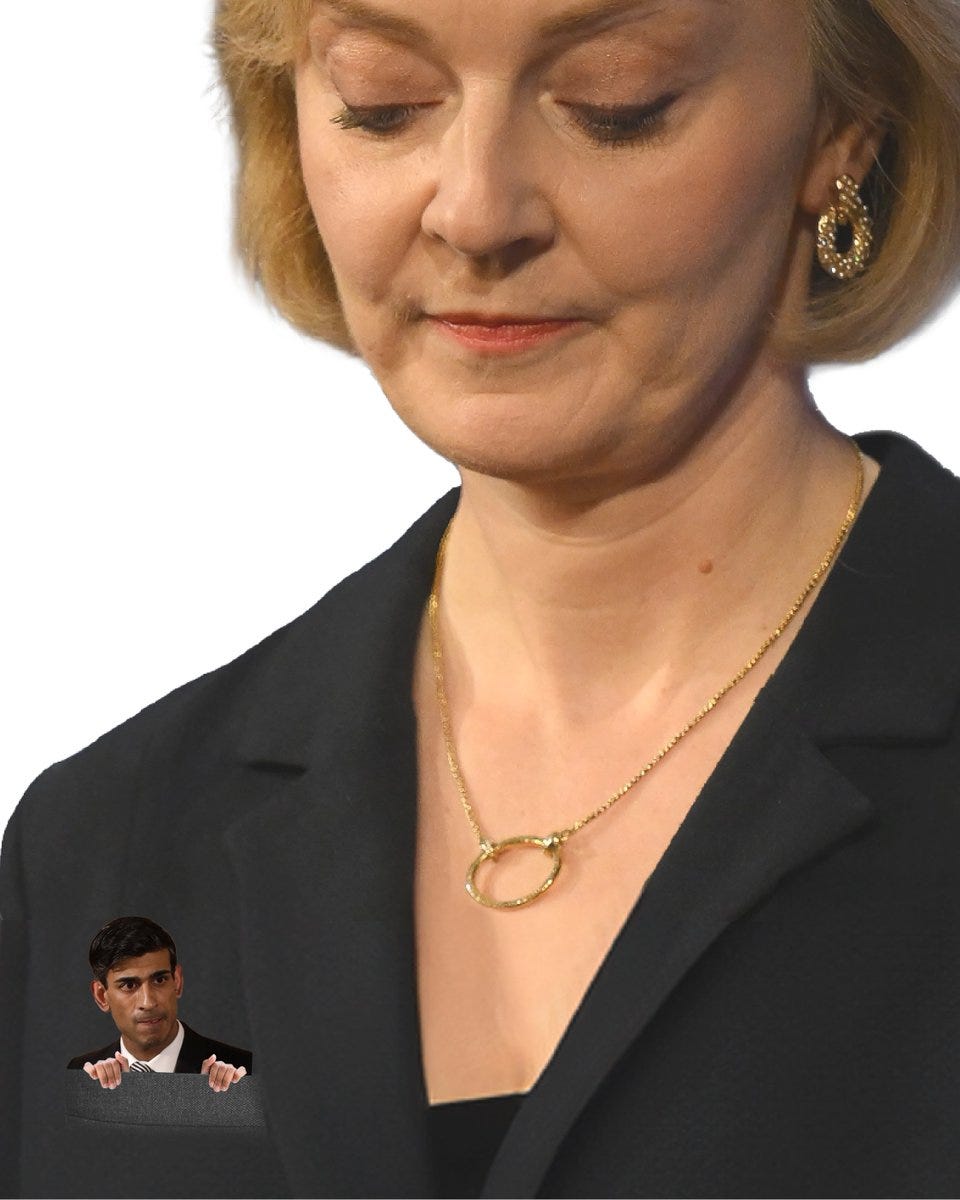

Is Rishi Sunak in Liz Truss’s pocket? That’s what the Labour Party would like you to think, according to a graphic they tweeted at the beginning of this month, with the caption “We know who’s really in charge”. But come off it. Rishi Sunak, who took on and lost to Liz Truss in a leadership election, refused to serve in her cabinet and then, on replacing her as Prime Minister, reversed most of the policies she announced in her 49 days in the job, isn’t taking orders from Liz Truss. Is he? And Liz Truss, who has so far spent a post-premiership which has a good chance of lasting more than half of her entire lifetime complaining that nobody is taking her ideas seriously, isn’t secretly running the government. Is she?

I think this attack - this precise attack, though, and not a superficially similar one I’ll discuss later - does work, and here’s why.

In my previous Substack post, I discussed the importance of political parties ensuring that their attack lines are both consistent with their positive messages and, well, true. (“True”, in this political sense, doesn’t mean absolutely, objectively, undeniably true - in politics, everything is contested - but credible, evidenced and in line with other things you are saying.) How can this attack be true? And what’s going on?

There are two small reasons for this attack, and for this graphic, which are worth mentioning because they’re real, but they’re not the main point here. First, it’s funny. Funny things are memorable, and more likely to get shared, and - never underestimate this as a motivation for the people who actually work on this stuff - fun to do. And, crucially, you can’t rebut a joke. Labour has got quite good at funny recently. See for example this graphic which they put out after the Department for Education posted an update on crumbling concrete in schools claiming “MOST SCHOOLS UNAFFECTED”:

Second - and you’ve spotted this already - this is an obvious parody of a Conservative poster from 2015 showing Ed Miliband in Alex Salmond’s pocket. One thing political operatives particularly love doing if they can is throwing an attack that worked on them - and this Tory attack on Labour really worked - back on their opponents. It’s cathartic.

But as I say, those are small reasons and neither is the main point. The reason Labour wants to talk about Liz Truss is that Labour wants to talk about Liz Truss. And Labour wants to talk about Liz Truss for the same reason the Conservatives want to talk about Jeremy Corbyn. Both main parties have current leaders whose strengths and weaknesses we can discuss, who can come across as a bit dull, but who do pass a basic test of looking as if they can more or less do the job. And both of these leaders’ immediate predecessors can plausibly be described as the worst leaders their parties have ever had (I’m not looking for an argument about this; if you think that either Corbyn or Truss were successful that’s fine, but please take it up with the electorate and the markets, respectively). Whenever the Tories can remind voters of Corbyn, and Labour can remind voters of Truss, they will.

However, the links the two parties can draw between their opponents’ current leaders and their previous ones are not quite equivalent. For the Tories, what connects Keir Starmer to Corbyn is that the former served in the latter’s shadow cabinet, and praised him during his leadership election campaign, before repudiating him later. It is not plausible to cast Starmer as a closet Corbynite - although the Tories have sometimes tried - and they cannot claim that Starmer is either close to Corbyn now or too weak to stand up to him. But they can use his past behaviour and comments as evidence of opportunism (one positive reading of this, as provided by Phil Collins in the Times this week, is that Starmer is simply a good politician; your mileage may vary on how far you see this as a plus point).

For Labour, what connects Sunak to Truss is not real or fake loyalty, but weakness. That’s how the “in the pocket” attack works. The “Miliband in Salmond’s pocket” attack was not a claim that Ed Miliband secretly wanted Scottish independence, but that he would be too weak in office not to succumb to SNP pressure. Similarly, the argument goes, Sunak is in Truss’s pocket because his party is. His freedom to manoeuvre is limited by a bloc of his parliamentary party, and a majority of his grassroots members, who agreed with her when they elected her a year ago and still agree with her now. And even if he has changed course on some of her policies, he has been reluctant to criticise her by name: a man who wants to be a change candidate, but who daren’t say except in the vaguest terms what he’s changing from. Weak, weak, weak. I lead my party, he follows his.

Labour sometimes overstates this - Sunak’s recent u-turn on net zero may be something Truss agrees with, but it seems to have been motivated by his own sincere belief that the previous policy was wrong - but the basic point is more than defensible.

Look how Truss made herself the star attraction at Conservative conference this year simply by turning up and being treated by the members as the star attraction. Look at the Tory MPs calling for tax cuts now. Even resisting those calls draws attention to the fact that there is a Liz Truss-shaped centre of gravity in the internal Conservative Party debate about policy. And Truss herself, with a heroic disregard for the impact her own record in office has on her ability to act as a credible advocate for anything, is evidently keen to be part of that debate, and to show that she and her ideas have not gone away - which, conveniently, is precisely the argument Labour wants to make to voters.

You can see the “Sunak is weak and Truss proves it” argument in Rachel Reeves’ conference speech last week (alongside a lovely little “Labour has changed” dividing line in her description of the Tories at their conference “queueing to cheer the extremists rather than kicking them out of their party”):

Liz Truss might be out of Downing Street but she is still leading the Conservative Party.

…

Rishi Sunak had the chance to denounce the politics and policies of Liz Truss.

To make clear that he would never repeat her mistakes.

But he didn’t.

If he’s too weak to stand up to them one year in – what chance do you give him five years in?

Be in no doubt: the biggest risk to Britain’s economy is five more years of the Conservative Party.

But there are ways of reminding voters about Truss that don’t go to weakness, but to something less powerful and less convincing. Labour reportedly wanted to use - and were prevented from using - the same image of Sunak in Truss’s pocket on a giant billboard overlooking Conservative Party Conference this year, with the caption “13 YEARS OF THE TORIES, YOU’RE STILL PAYING THE PRICE”.

But that’s not the right caption, is it? “We know who’s really in charge”, the caption the used in the tweet I discussed at the start of this post, is the right caption. This caption makes a different, worse argument that doesn’t fit the image. It’s the same argument as the one in this graphic, tweeted by Labour earlier this month, showing Rishi Sunak looking in the mirror and seeing Liz Truss looking back at him:

At first glance, this - Sunak and Truss in the same picture - can look like the same attack as the one in the graphic we started with. But it isn’t. This isn’t about a power relationship. It isn’t a claim about Sunak’s weakness. It’s a simple claim that they are the same: one looks in the mirror and the other looks out. That’s despite the fact that Sunak fought a leadership contest against Truss, in which they had a number of substantive disagreements on policy, and - a sign of weakness - lost.

The problem with this attack isn’t just that it isn’t true. It’s that it isn’t as good as the truth. The astonishing inconsistency of policy over the last thirteen, and especially the last five, years of Conservative government is a real mark of failure and incompetence, genuinely bad for the country, and a compelling rebuttal of Rishi Sunak’s claim to be offering Long-Term Decisions For A Brighter Future. Labour shouldn’t pretend it’s all the same, because the reality is even worse: it’s all different. I get why they want to go there, and “Same Old Tories” is a tried and tested, if often not a winning, line. But the main thing the Same Old Tories have done with consistency over the decades is win elections. Labour had better hope they’ve changed.

Dividing Lines has a relatively narrow focus - political attack - for two reasons. First, I think it will be easier for me to think of things to write about if I’m clear to myself that I don’t just write about any old stuff that takes my interest: that’s what Twitter is for. And second, I sincerely believe that political attack is interesting: that it tells us a lot about politics, about how politics works and why parties succeed or fail, about whether political parties are effective or dysfunctional, and above all what a party’s argument is - and I’ve always been fascinated by arguments. You can’t attack your opponent well if you don’t know what you think or why you think it: what you think about them, but also about yourselves. Attack reveals strategy, or lack of it. So Dividing Lines is about strategy, and argument, and policy, and party management, and leadership too. But attack is the way in.

If you’ve seen an example of political attack material that you think is good, or bad, or interesting, and you’d like me to write about it, let me know (if you subscribe to Dividing Lines - and please do subscribe - you can just hit reply). I’m not going to promise to take requests, but I’m going to need stuff to write about. Also, feedback is good, except when it’s bad.